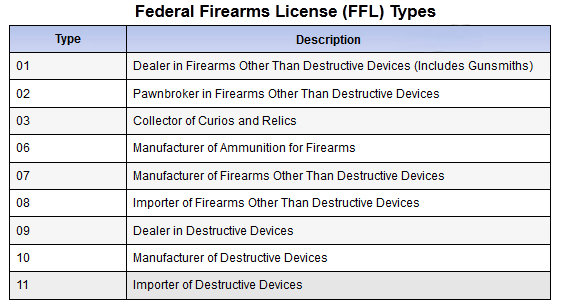

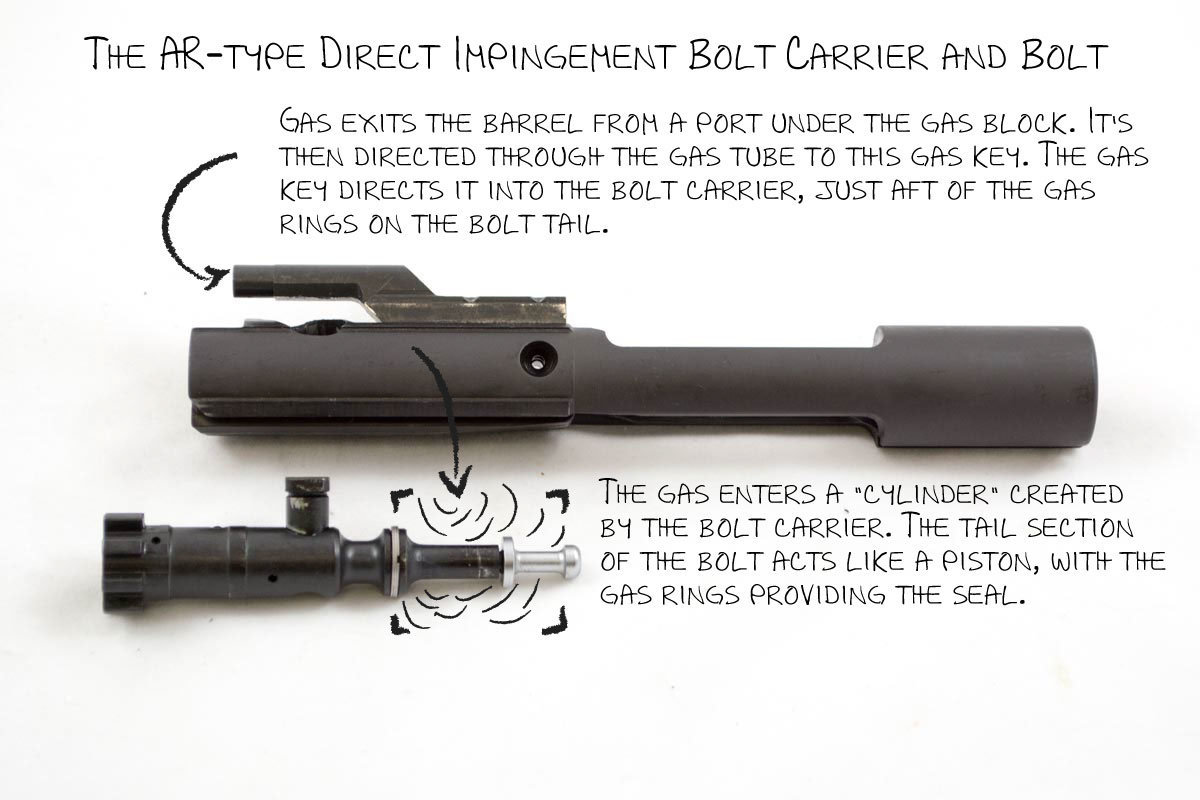

Imagine the bolt (below) inside of the bolt carrier (above) and you can see how the gas flow works.

We’re on to part three in our series on how to build an AR-15, and

this one is important. We’re going to get technical. If you’re new to

this series, I’d like to suggest you read the introduction. If you’re

serious about building an AR, it will let you know what you’re getting

into.

Part 1:

Build an AR-15: The Series Introduction (Why Build Your Own AR)

And before you start buying parts, you should understand what you

want the rifle to do. Is this going to be a 5.56 rifle? A .300 blackout?

Are you wanting to build the most versatile multi-caliber lower

possible?

Part 2:

Build an AR-15: AR Calibers (Or is 5.56 really the right choice?)

All AR-type rifles have plenty of gas; they just deal with it differently.

Eugene Stoner had plenty of gas. So much so that he designed his

AR-15 semi-automatic rifle to work entirely on gas flow. The method of

operation was called direct impingement. Well, people refer to it as

direct impingement, but it’s really a little bit different. We’ll get

into that nitty gritty minutia in a bit. For now, just envision those

nifty lug wrenches at tire stores that are powered completely by

compressed air. It’s a similar concept.

But, as a fellow gun person, you know how we like to tinker. It

doesn’t matter if something works or not; we’ve just got to tweak modify

and try to improve things. Our collective experimentation has created

another type of system for AR-type rifles. That would be piston

operation. We’ll explain that in detail in a bit also.

Direct Impingement Operation

I’m going to use the term “direct impingement” here, but only because

everyone else does, and it’s commonly known. Technically, Eugene

Stoner’s original design is really more like an internal piston that

operates inside the bolt carrier. Think of this comparison, and we’ll

keep our analogies a little loose for simplicity.

In a pure direct impingement scenario, imagine blasting a jet of

compressed air at a lever, like maybe a light switch. With enough air

pressure, you’re going to bash the switch hard enough to move it to the

opposite position. That hammering like motion with gas it sort of like

true direct impingement.

Here’s the barrel gas port, formerly under the front sight and gas block, which has been removed.

With an internal pistol system, you’re filling the inside of a

cylinder with expanding gas. As pressure builds, it’s gonna want to move

the piston in the direction of least resistance. Again, with a slightly

inexact analogy think of this scenario like a gas engine piston moving

as the gas vapor ignites and increases the pressure inside of the

cylinder.

Let’s look at exactly how this “direct impingement” or “internal piston” works in an AR-type rifle.

When you fire a cartridge, a veritable boatload of hot and expanding

gas pushes the bullet down the barrel. It’s under really big pressure,

starting at somewhere around 60,000 pounds per square inch. Of course,

that pressure level rapidly declines as the volume between the cartridge

base and bullet rapidly increases as the bullet moves down the barrel.

The section of the barrel between the chamber and bullet at any given

microsecond represents the available volume. And from high school

physics, some famous smart guy stated that as volume increases, pressure

has to decrease, all else being equal. I think it was Ben Cartwright

before he opened that ranch on Bonanza.

Part way down the barrel (the exact position varies depending on the

“gas system length” of the rifle in question) there’s a tiny hole that

lets gas escape into what’s commonly referred to as the gas block. In

original AR-type rifles with the triangular fixed sight, the gas block

is contained within the sight assembly, so you really don’t see it as a

separate piece. Part of the function of the gas block is to redirect

some of the gas back towards the action of the gun. The gas is moving

towards the muzzle, then straight up through the hole in the barrel. The

gas block redirects it through a gas tube that leads back to the

receiver. If you look through holes of the hand guard on an AR-type

rifle, you’ll see a (usually) silver tube running between the front

sight or gas block and receiver.

On

a direct impingement AR-type rifle, the gas tube connects to the gas

block and/or front sight and directs gas back to the bolt carrier group

in the receiver.

This tube ends at what’s called the gas key on the bolt carrier. The

key fits over the gas tube and redirects the gas into the interior of

the bolt carrier where it can move the bolt itself. Here, the bolt and

carrier act pretty much like a piston (the bolt tail) and a cylinder

(the bolt carrier.) The gas enters the bolt carrier and fills a chamber

created by the space between the gas rings on the bolt and the internal

wall of the bolt carrier where the firing pin body is located.

As gas enters this “cylinder” area, it pushes the bolt in the

direction of least resistance, which is actually forward, sort of. In

the locked position, the bolt is pressed all the way into the bolt

carrier. The expanding gas moves it forward and the carrier backward, so

the bolt rotates as the cam pin follows the angled path of the cam pin

slot. Once the bolt partially turns and unlocks from the barrel

extension, it has nowhere else to go, so the gas pressure inside of our

“cylinder” pushes the bolt carrier backward further towards the recoil

spring. The bolt carrier movement drags the bolt with it, causing

ejection of the round.

At some point, the resistance of the buffer spring overpowers the

declining gas pressure and starts to move the whole assembly forward

again, picking up a new round in the process. The bolt carrier and bolt

slam into the barrel extension and pressure pushes the bolt back inside

of the bolt carrier, rotating due to the cam pin slot. The bolt locks

into position, and you’re ready to fire another shot.

That’s quite a lot happening in a small fraction of a second. In the

context of direct impingement versus piston operation, it all boils down

to this. The bolt itself is a piston. The bolt carrier is a cylinder.

Rather than a “gas jet bashing motion” the operation is a more gentle

expansion in a cylinder that results in movement. Of course, “gentle” is

a relative term. Hot and dirty gas flows directly into the bolt

assembly causing movement, extraction, hammer re-cocking and chambering

of a new round. Don’t let the “hot and dirty gas in the bolt” concern

you too much, as it’s a largely self-cleaning system. I don’t mean you

don’t have to clean your rifle. I simply mean that gunk doesn’t build up

infinitely on the interior of the piston and cylinder surfaces.

Piston Operation

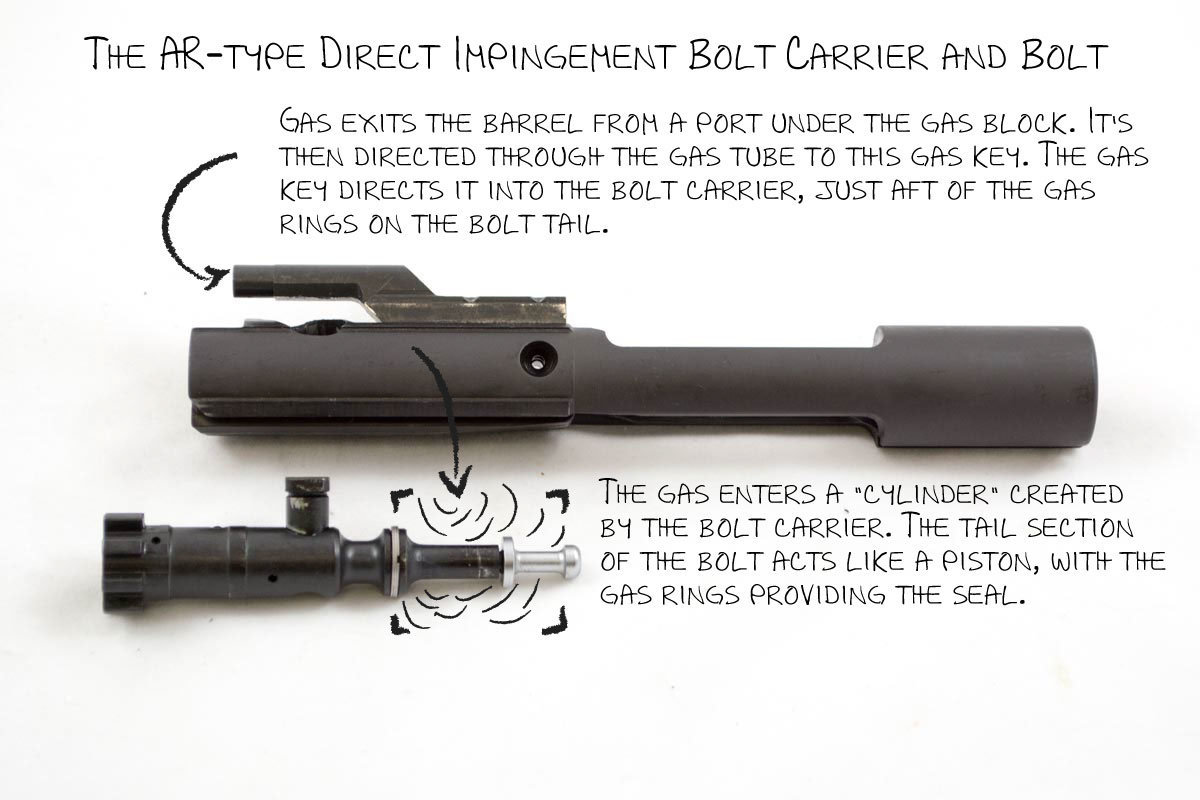

With piston operation, the interface between hot expanding gas and moving parts happens far away from the bolt itself.

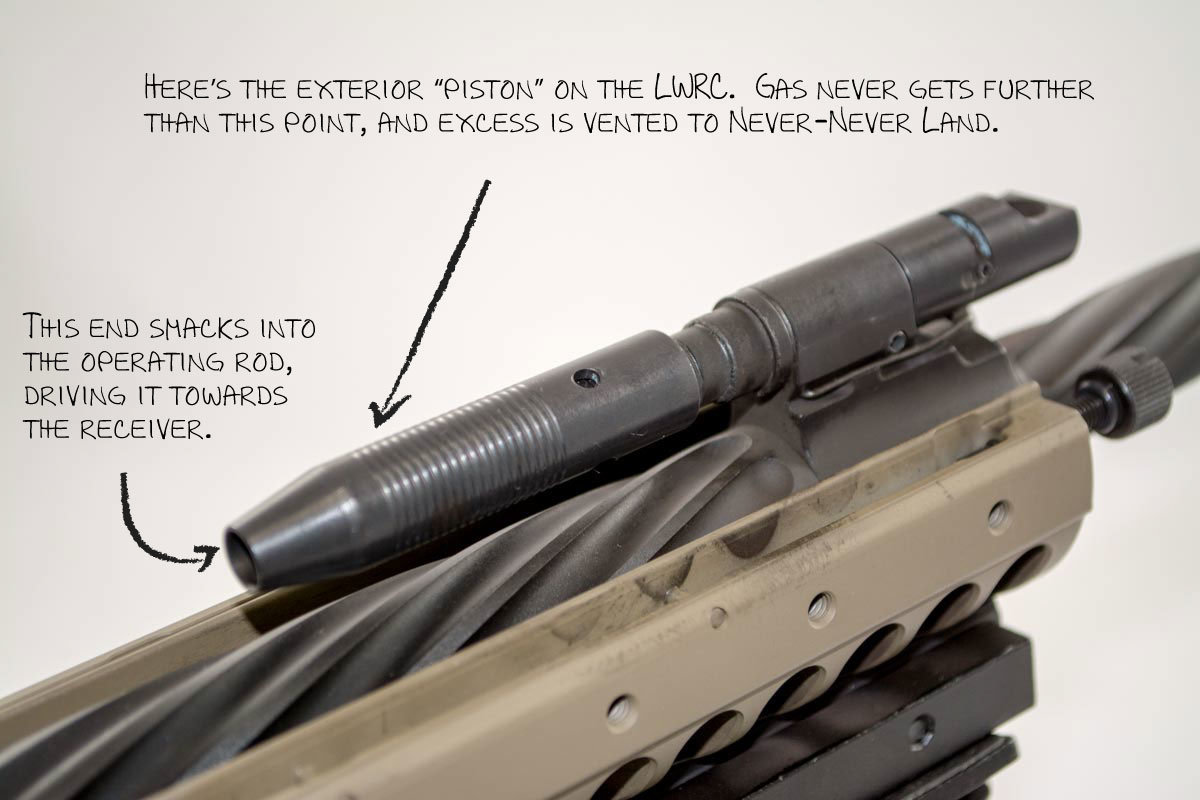

The fully installed gas piston and operating rod on the LWRC.

When you fire a shot, hot, high-pressure gas moves down the barrel,

driving the bullet forward. Piston guns still have a small gas port in

the barrel that allows some of the expanding gas to move into a gas

block.

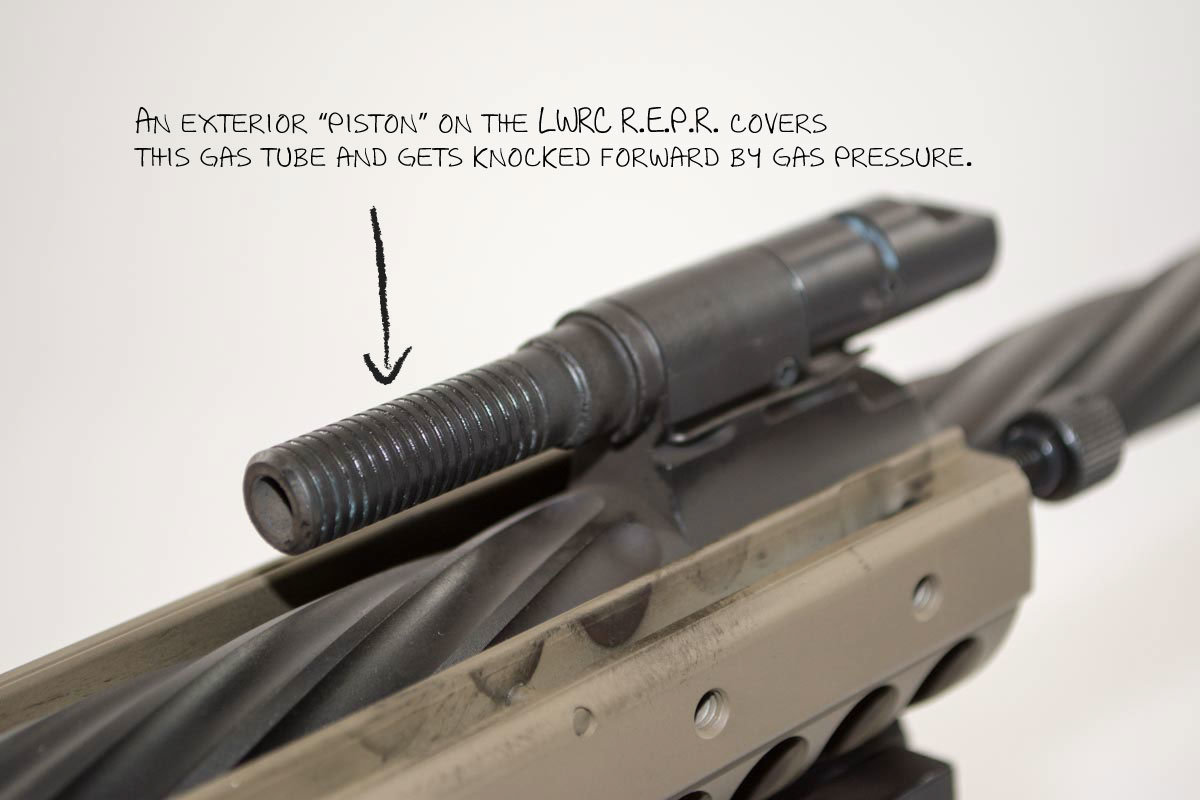

Here’s where the differences between the two systems begin. Rather

than directing the gas all the way back to the receiver, the block

directs the gas into a cylinder above the barrel. Inside of this

cylinder is a piston that moves forward from the gas pressure.

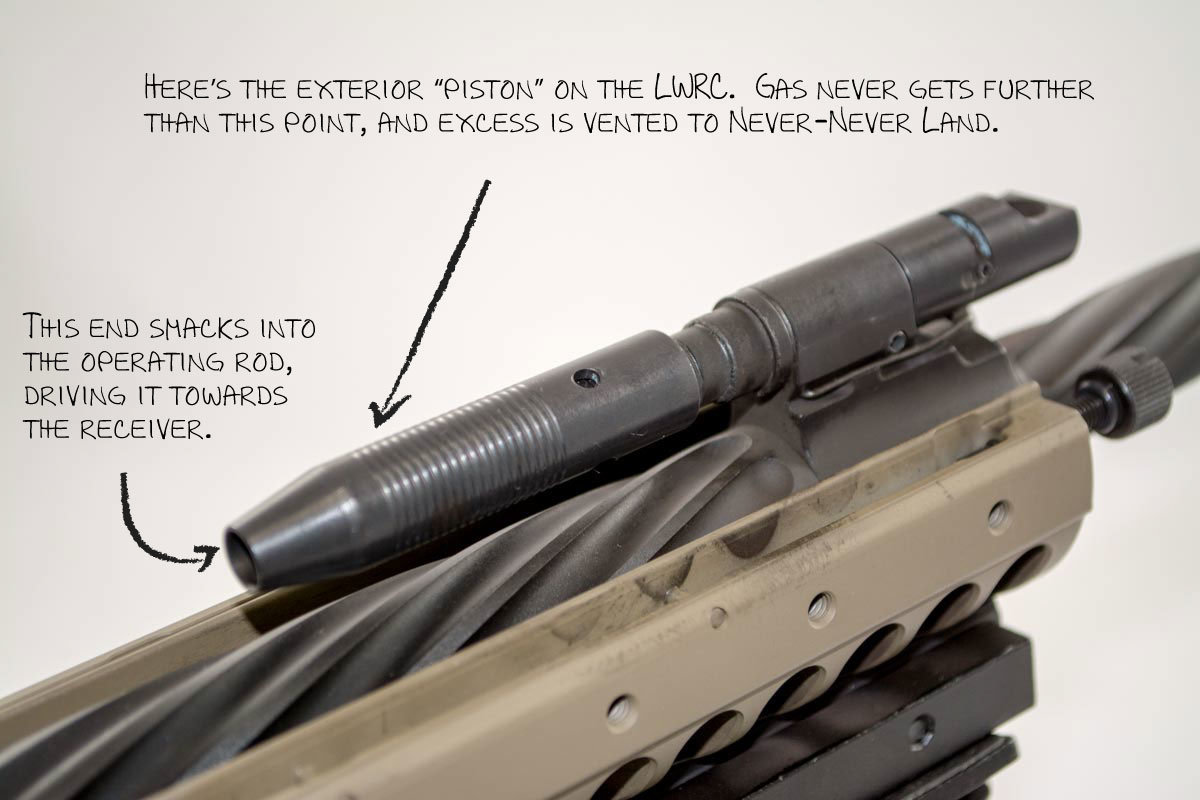

This is as far as dirty gas gets on this particular pistol operated rifle.

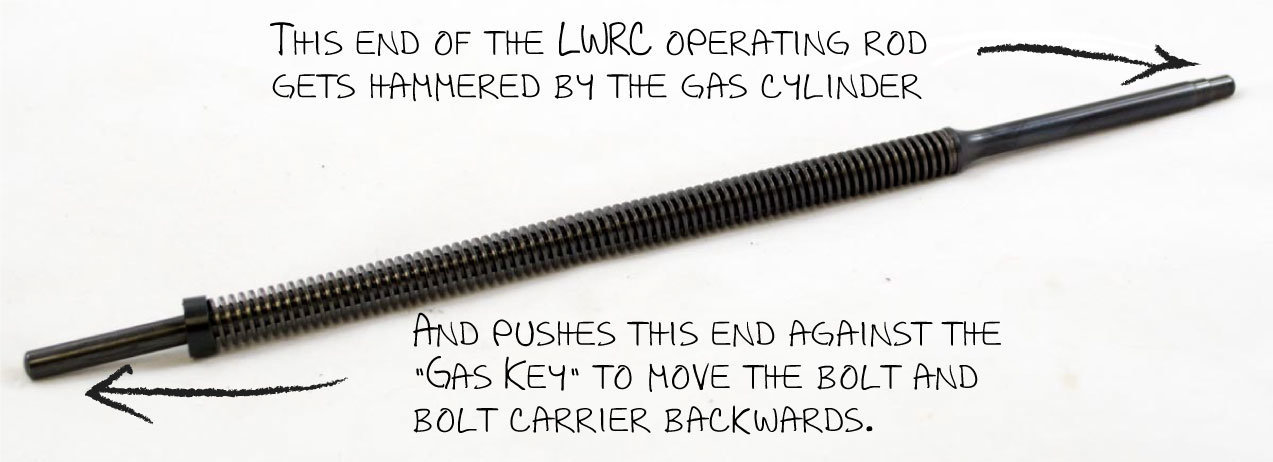

With most designs, the cylinder impacts some type of operating or

connecting rod, which carriers the movement back to the bolt carrier

group.

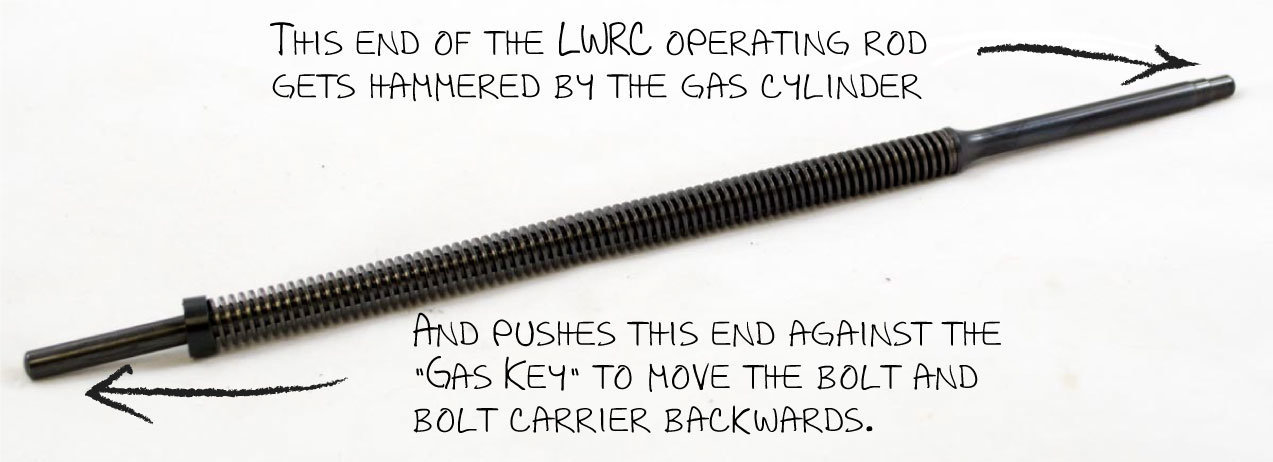

The piston without operating rod installed.

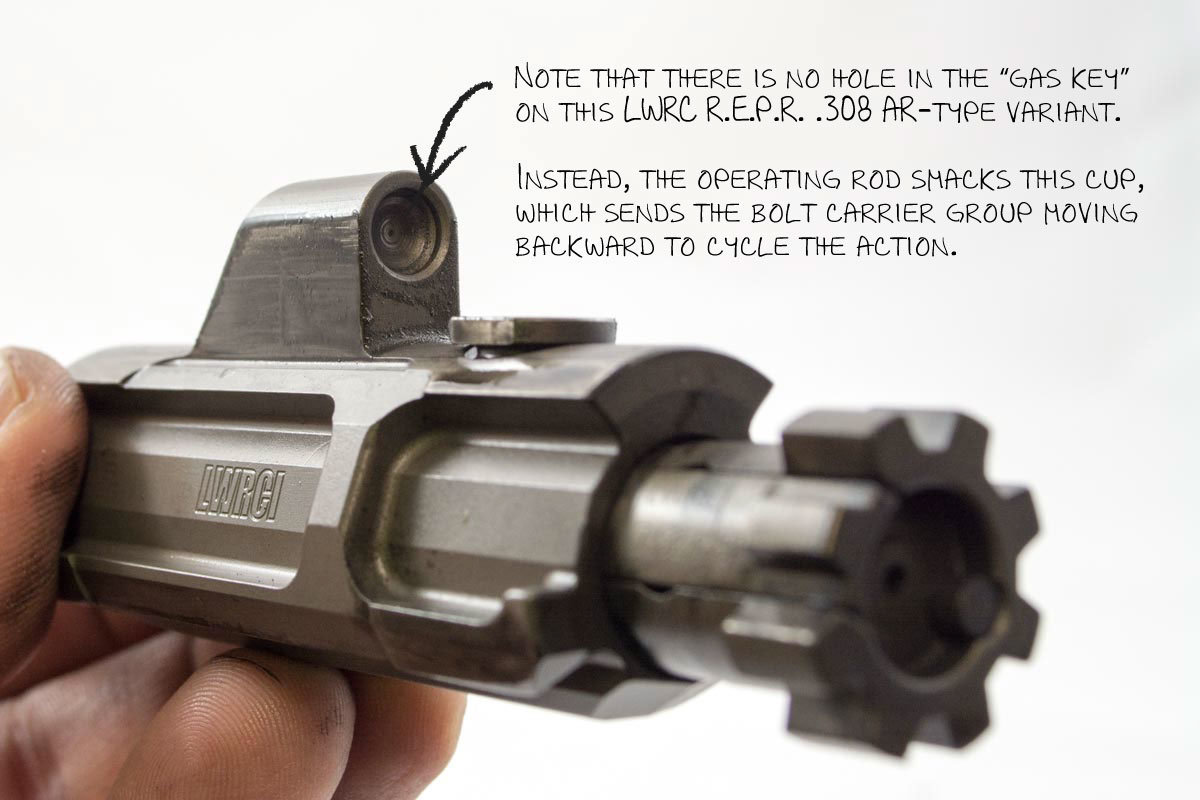

On an AR-type rifle, the connecting rod impacts a modified gas

carrier key. On the direct impingement gun, the gas key just directs the

flow of gas to the bolt. On a piston gun, the “gas key” equivalent part

takes the hit from the connecting rod and pushes the bolt carrier group

backward, initiating the same function as with a regular AR-type rifle.

Note how clean this operating rod is. That’s because hot and dirty gas never touches it.

The net-net of the piston system is that the bolt is moved via impact

of a metal rod rather than flow of gas into the bolt carrier. The bolt

and carrier do not operate as a piston and cylinder – those equivalent

parts are located far forward above the barrel.

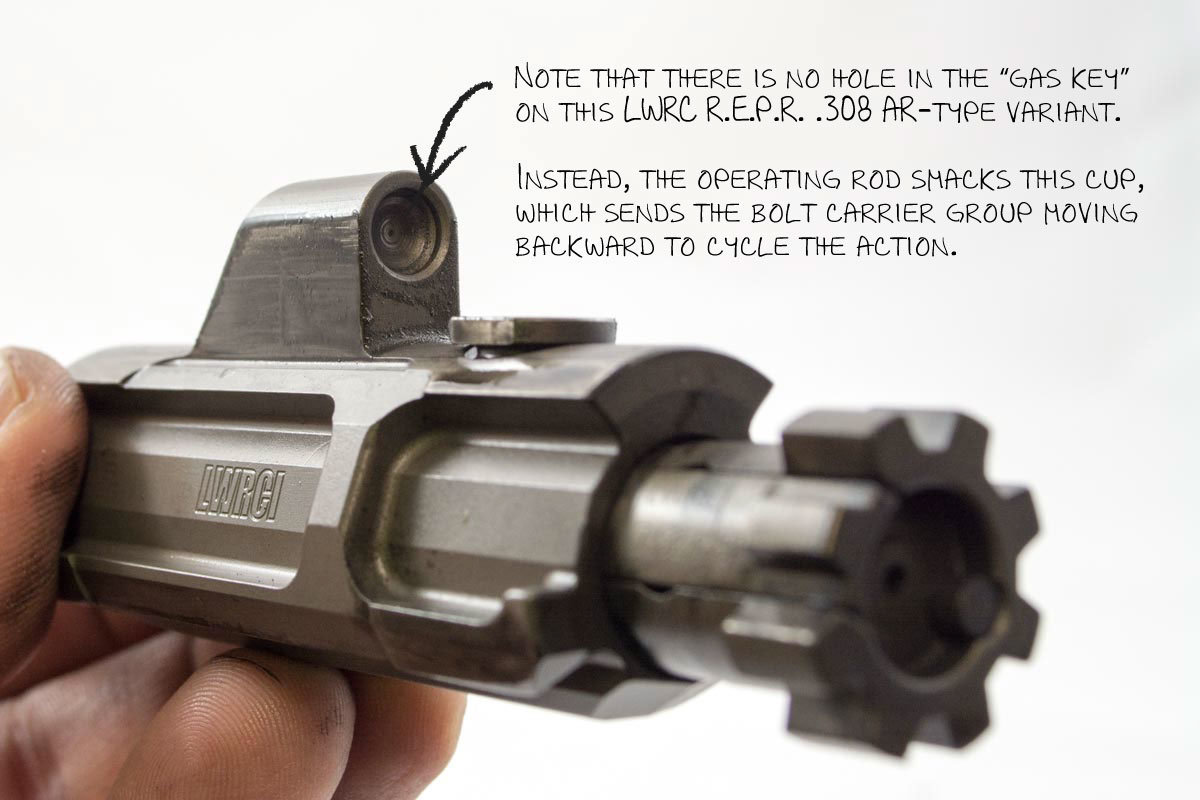

Here’s the LWRC R.E.P.R. “gas key” which really has nothing to do with gas at all.

Pros and Cons

Cleanliness is next to… piston operation?

The direct impingement haters can’t stand the fact that hot, dirty

gas blows right into the action of your rifle with each and every shot.

That just sounds bad, right?

Of course, there is truth to this. Hot and dirty gas DOES, in fact,

go straight into the bolt area. The real question is, how much does that

matter? In my view, not much. The system is designed that way and

offers plenty of offsetting advantages which we will touch on elsewhere

in this section. As mentioned earlier, the carbon build up on the boat

tail is largely a self-cleaning scenario. In terms of other cleaning and

maintenance, there are fewer moving parts in a direct impingement

system, so there are fewer parts to get dirty to the point of

malfunction.

This

bolt hasn’t been cleaned yet and has hundreds of rounds of .308 through

it. Note how clean a piston system keeps the bolt and carrier.

With piston designs, the gas moves a piston located far from the

action. After the gas does it’s work, excess is vented to the great

outdoors. The net result is that the bolt and carrier area stays pretty

darn clean, making your cleaning chores fewer and farther between. On

the flip side, you now have parts up front, under the hand guard, that

are subject to other types environmental dirt and subsequent jamming.

From a reliability related to cleanliness standpoint, I would

consider the two designs a wash. You have different types of “dirt risk”

for any type of rifle. The bottom line is that you still need to

maintain your gun properly.

Temperature

In a traditional direct impingement AR-type rifle, the gas that

enters the bolt and carrier area are HOT. Predictably, those parts, and

the surrounding upper receiver, get hot pretty quickly. Unless you’re

planning to pull the bolt and carrier out with your bare hands

immediately after unloading a few magazines, this isn’t a huge deal. Of

course, hotter temperatures can break down lubricants faster, so you

will need to pay more attention that and use high quality,

temperature-resistant gun oils.

On a piston gun, the action stays surprisingly cool. Of course, the

chamber will get hot and bleed heat into surrounding areas, it just

takes a lot more shots to get the bolt and carrier area to the same

temperature level.

Suppressor use

There are a lot of theoretical arguments about which platform is

better for suppressor use, but my view is far more practical. If you use

a suppressor, your gun will get filthy, regardless of whether it’s a

direct impingement or piston operated model.

Many piston systems offer adjustable gas features which let you

decrease the amount of gas fed into the system for suppressor use, or

increase the amount of gas for adverse conditions. The extra gas flow

makes things work even when dirty, to a degree.

Accuracy

Here’s where potential fighting words start. While I won’t (and

can’t) make a definitive claim that traditional direct impingement

rifles are more accurate, it’s been my experience that they are.

Disclaimer: I have NOT tested enough rifles of both types under strictly

controlled conditions to make that claim, it’s just what I have

observed over time. I suspect this is for a variety of reasons.

The direct impingement system is a very smooth operation. The flow of

gas to the bolt and carrier creates no movement of parts until it

enters the cylinder (bolt carrier.) The forward and backward motion of

the bolt and carrier is very linear, with no torque or off-center force.

To oversimplify, it’s a very smooth action. Piston guns have moving

parts along the way, and the force that moves the bolt carrier is “off

center.” The connecting rod applies backward motion to the modified gas

key on the bolt carrier, potentially creating a non-linear pushing

motion. Manufacturers have come up with various solutions to mitigate

this, but it’s still at last a theoretical issue. While the bullet is

gone by the time all this happens, many folks believe the linear action

of the direct impingement system does improve bolt locking and

unlocking, which can affect accuracy.

Overall mass might come into play also. The extra piston and

operating rod components add weight. And movement of mass during firing

cause overall movement. While the bullet is gone by the time things

really start to move, this shift mass can force the rifle off target

between shorts more than with a direct impingement model.

Standardization

The classic direct impingement AR-type rifles (usually) have

interchangeable parts as they follow the design on the original AR-15.

Generally speaking, parts are easy to come by from a variety of

manufacturers.

Piston designs are generally proprietary. Everyone has a slightly

different design, so parts are usually not interchangeable. You’ll

almost always have to get replacements and support from the manufacturer

of your rifle components.

Which One Should You Build?

Unfortunately I can’t just tell you the answer. Like most things

gun-related, much depends on the intended use and your personal

preferences. In my opinion, neither is “better” than the other. It’s

just like pizza. Double-cheese and Italian sausage isn’t “better” than

triple-cheese and pepperoni. It’s just different. Yes, I like lots of

cheese on my pizza, but that’s beside the point.

Decide what features you care about for your anticipated type of use.

Consider how some of the pros and cons discussed here might impact that

way you’re going to use your gun. The good news is that there is no

right or wrong decision – it’s really a matter of pizza.