Recently we introduced the whole concept of the mil-dot (or milliradian) system for rifle scopes in Mil-Dot Made Easy.

In that article, we got into the practical application of how mil-dot

scopes can be used to figure out how to aim at a distant target. With

simple math, you can figure out how much adjustment to make to your

optic to account for bullet drop at longer ranges. The same system can

be used to calculate windage adjustment to account for crosswinds and

figuring out how much to lead a moving target.

That’s all fine and cool, but what I like most about the mil-dot system is that it can be used to figure out the distance to a target, just by looking through your optic. Hey, when the Zombies come, batteries are going to be in short supply, and those fancy laser rangefinders will only work for so long.

In fact, one of the earliest uses of the mil-dot ranging system allowed submarine commanders to figure out how far away an enemy ship was. This knowledge, used with some basic math that factored in the speed of their torpedoes, told them where to aim in order to intersect the path of the ship. If you’re ancient enough (like me) to have played that old arcade game Sea Wolf, you’ll know the concept. Except back then, you had to guess when to launch the torpedo, and it took a lot of quarters to nail the timing consistently. If you don’t know what an “arcade game” is, count me as envious of your youth.

Likewise, mil-dot markings in your scope can easily be used to figure out how far away a person, animal, or object is from your current position. It’s a matter of proportion. For example, have you ever tried to help someone spot a planet in the night sky by telling them something like, “Look two thumb widths over from the moon and you’ll see it?” Obviously, Mercury is somewhat farther than two thumbs away from the moon. Your thumb width is just represents a proportional distance relationship. The width of your thumb two feet from your eyes represents some millions or billions of miles of distance far out in space.

The concept of determining how far away something is using mil-dots is similar. Because the proportional size of an object is constant with distance, you can use some basic algebra principles to figure out the range. Don’t freak out because I used the word “Algebra!” I hated that class too, but there is one important thing we all learned that applies here. Remember “solving for X?” All that really boiled down to was knowing that if there are three pieces of information, and you know two of them, you can usually solve for the missing third one. In this case, you can always solve for the missing piece of info at the relationships are proportional.

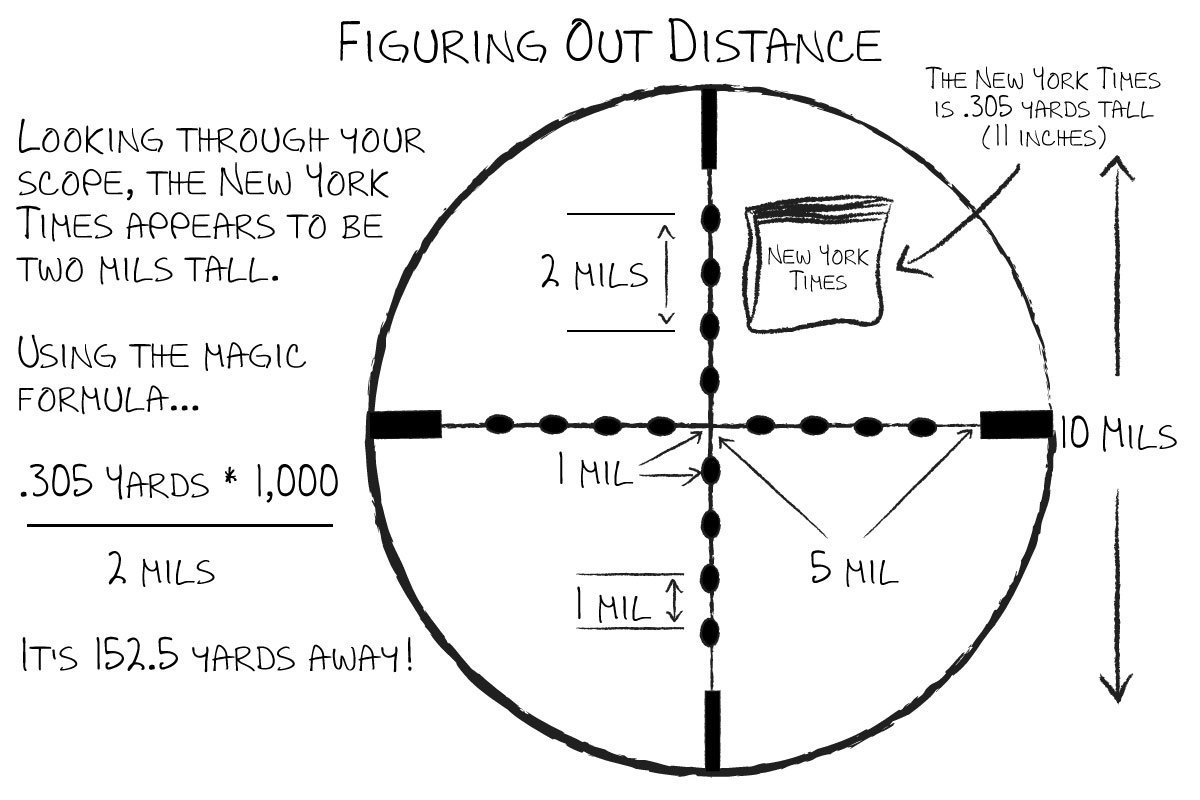

At risk of grossly oversimplifying math and ticking off my 8th-grade algebra teacher, it works like this. With a mil-dot scope, we know that the measurements between dots on the scope reticle equate to 1 yard at 1,000 yards distance. If we also know the actual size of a distant object, like a person standing, fence post, or copy of the New York Times, then we have two pieces of known information. The only thing missing is the distance between our scope and the known size object.

Let’s use a real-world example to illustrate the idea.

Suppose we want to shoot a copy of The New York Times. Yes, that brings me joy, but that story is for another day. Someone has placed it down range at an unknown distance. As hardly anyone knows, the width of The New York Times is about 12 inches. When folded, as it would be in a newspaper rack, it’s about 11 inches tall. Now, if someone put our example entirely objective content newspaper at close range, say 5 feet, it would look pretty big through a scope. However, if they placed it 300 yards down range, it would appear to be a puny little thing, even less worthy of a read than normal. That’s the whole proportion thing in action. They farther away it is, the smaller it appears.

Here’s where the magic of mil-dot comes into play. What if we “measured” the size of our downrange newspaper using the mil-dot markings in the scope? Using the scope marks like a ruler, we can look at the paper through the scope and see how many “mil-dots” in the scope reticle it covers. At close range, say 10 yards, the paper might appear to be 20 mil-dots tall. At long range, it might only be one or two mil-dots tall. Here’s where we can use our two “known” pieces of information to figure out how far away it is. We know the length of a mil-dot at a fixed range of 1,000 yards. We also know that the New York Times, when folded, is about 11 inches tall. The only piece of missing information is the distance between us and the formerly-epic example of investigative journalism.

Here’s where the proportions come into play. Remember from the previous discussion that one milliradian (mil) equates to one yard at a distance of 1,000 yards. For illustration’s sake, imagine standing a yardstick upright 1,000 yards down range. When we look at that through a mil-dot scope reticle, it will appear to be exactly one mil tall.

That’s the basis of the proportion relationship. If a one-yard tall object appears to be one mil tall through the scope, it must be 1,000 yards away. If it appears to be two mils tall, then it’s only 500 yards away. If the object is not exactly one yard tall, then you need to adjust accordingly.

Let’s say that The New York Times appears to be two mils tall through our scope. But we know that it’s only .305 yards tall. We also know that a one-yard tall object that appears to be two mils tall through the scope is 500 yards away, so a smaller object that appears two mils tall must be closer, since it appears larger.

Rather than get all wrapped up in the words, there’s a simple formula to figure out the range. It relies on knowing the actual size of the object your are ranging and the number of mils that it appears to be through your scope.

Plugging these values into the formula, we get:

The same formula works with meters too, as long as you’re consistent.

It sounds complicated, but once you get the hang of it, you can use this system almost anywhere, because there are almost always objects of known size nearby. For example:

That’s all fine and cool, but what I like most about the mil-dot system is that it can be used to figure out the distance to a target, just by looking through your optic. Hey, when the Zombies come, batteries are going to be in short supply, and those fancy laser rangefinders will only work for so long.

In fact, one of the earliest uses of the mil-dot ranging system allowed submarine commanders to figure out how far away an enemy ship was. This knowledge, used with some basic math that factored in the speed of their torpedoes, told them where to aim in order to intersect the path of the ship. If you’re ancient enough (like me) to have played that old arcade game Sea Wolf, you’ll know the concept. Except back then, you had to guess when to launch the torpedo, and it took a lot of quarters to nail the timing consistently. If you don’t know what an “arcade game” is, count me as envious of your youth.

Likewise, mil-dot markings in your scope can easily be used to figure out how far away a person, animal, or object is from your current position. It’s a matter of proportion. For example, have you ever tried to help someone spot a planet in the night sky by telling them something like, “Look two thumb widths over from the moon and you’ll see it?” Obviously, Mercury is somewhat farther than two thumbs away from the moon. Your thumb width is just represents a proportional distance relationship. The width of your thumb two feet from your eyes represents some millions or billions of miles of distance far out in space.

The concept of determining how far away something is using mil-dots is similar. Because the proportional size of an object is constant with distance, you can use some basic algebra principles to figure out the range. Don’t freak out because I used the word “Algebra!” I hated that class too, but there is one important thing we all learned that applies here. Remember “solving for X?” All that really boiled down to was knowing that if there are three pieces of information, and you know two of them, you can usually solve for the missing third one. In this case, you can always solve for the missing piece of info at the relationships are proportional.

At risk of grossly oversimplifying math and ticking off my 8th-grade algebra teacher, it works like this. With a mil-dot scope, we know that the measurements between dots on the scope reticle equate to 1 yard at 1,000 yards distance. If we also know the actual size of a distant object, like a person standing, fence post, or copy of the New York Times, then we have two pieces of known information. The only thing missing is the distance between our scope and the known size object.

Let’s use a real-world example to illustrate the idea.

Suppose we want to shoot a copy of The New York Times. Yes, that brings me joy, but that story is for another day. Someone has placed it down range at an unknown distance. As hardly anyone knows, the width of The New York Times is about 12 inches. When folded, as it would be in a newspaper rack, it’s about 11 inches tall. Now, if someone put our example entirely objective content newspaper at close range, say 5 feet, it would look pretty big through a scope. However, if they placed it 300 yards down range, it would appear to be a puny little thing, even less worthy of a read than normal. That’s the whole proportion thing in action. They farther away it is, the smaller it appears.

Here’s where the magic of mil-dot comes into play. What if we “measured” the size of our downrange newspaper using the mil-dot markings in the scope? Using the scope marks like a ruler, we can look at the paper through the scope and see how many “mil-dots” in the scope reticle it covers. At close range, say 10 yards, the paper might appear to be 20 mil-dots tall. At long range, it might only be one or two mil-dots tall. Here’s where we can use our two “known” pieces of information to figure out how far away it is. We know the length of a mil-dot at a fixed range of 1,000 yards. We also know that the New York Times, when folded, is about 11 inches tall. The only piece of missing information is the distance between us and the formerly-epic example of investigative journalism.

Here’s where the proportions come into play. Remember from the previous discussion that one milliradian (mil) equates to one yard at a distance of 1,000 yards. For illustration’s sake, imagine standing a yardstick upright 1,000 yards down range. When we look at that through a mil-dot scope reticle, it will appear to be exactly one mil tall.

That’s the basis of the proportion relationship. If a one-yard tall object appears to be one mil tall through the scope, it must be 1,000 yards away. If it appears to be two mils tall, then it’s only 500 yards away. If the object is not exactly one yard tall, then you need to adjust accordingly.

Let’s say that The New York Times appears to be two mils tall through our scope. But we know that it’s only .305 yards tall. We also know that a one-yard tall object that appears to be two mils tall through the scope is 500 yards away, so a smaller object that appears two mils tall must be closer, since it appears larger.

Rather than get all wrapped up in the words, there’s a simple formula to figure out the range. It relies on knowing the actual size of the object your are ranging and the number of mils that it appears to be through your scope.

Plugging these values into the formula, we get:

The same formula works with meters too, as long as you’re consistent.

It sounds complicated, but once you get the hang of it, you can use this system almost anywhere, because there are almost always objects of known size nearby. For example:

- The average fencepost is about 4 feet (1.33 yards) tall.

- An “average” man standing is 70 inches (1.94 yards) tall.

- An average man sitting is 33 inches (.917 yards) high.

- A Russian T-72 Tank is about 1 yard from the ground to the base of the turret. OK, maybe we don’t all know the tread height of a T-72, but you have to admit, it’s an interesting factoid to file away. I didn’t know it either, and had to look it up.

No comments:

Post a Comment