US Surplus .50 BMG Full Metal Jacket, 709 Grain Ball M2, 2810 fps, 130 Rounds On Links in Bulk Case

Monday, July 20, 2015

US Surplus .50 BMG Full Metal Jacket, 709 Grain Ball M2, 2810 fps, 130 Rounds On Links in Bulk Case

US Surplus .50 BMG Full Metal Jacket, 709 Grain Ball M2, 2810 fps, 130 Rounds On Links in Bulk Case

Build an AR-15: The Lowdown on Lowers

Get caught up with the step-by-step series

Part 1: Build an AR-15: The Series IntroductionPart 2: Build an AR-15: AR Calibers

Part 3: Build an AR-15: Direct Impingement or Piston Operation

Part 4: Build an AR-15: Tools and Materials

Buy an AR-15 Lower Receiver on GunsAmerica: http://www.gunsamerica.com/Search.aspx?T=ar-15%20lower

The Garand continues to be popular thanks to groups like the CMP and Call of Duty games. But it wasn’t the logical choice for the wars of the late 20th century.

A brief and reductive history

As the dust settled from WW2, the powers-that-be accepted that our standard service rifle wasn’t the answer for unconventional warfare. The M1 Garand was simply too big, too slow, too limited. Battle rifles were a product of late 19th and early 20th century fighting styles. While there are a lot of die-hard fans of the Garand, most of them would hesitate to carry the weapon into war.We had fielded the M1 Carbine, which was easier to carry, but the .30 Carbine round had limited range and mediocre ballistic performance. There was a need for a rifle that took the best features of all of America’s sweet hearts and embodied them into one space age blaster.

But tradition dies hard. We had a brief detour with the M14, essentially a Garand-like rifle that used a box magazine and fired a slightly smaller round (.30-06 and 7.62×51). The prevailing belief suggested that we needed a rifle that fired a heavy projectile.

Even with significant upgrades (like the Juggernaut Rogue Bullpup Chassis), the M1A (Springfield Armory’s version of the M14) is a beast. Capable, yes, but in a different class than the slimmed down AR-15.

The rifle was sold to civilians as the AR-15 and was heavily marketed to the US military (and eventually adopted as the M16). In 1967, the M16 was officially adopted as the US Military’s service rifle. And it wasn’t a smooth adoption. For more on the controversy surrounding how the M16 launch catastrophically failed, I’d suggest reading C.J. Chivers’ book The Gun.

Rails, shorter barrels, flat top receivers, collapsible stocks, pistons… the weapon system changed as time progressed. One part, though, has remained fundamentally the same (at least until recently). The lower receiver is the heart of this gun and it is the reason why this rifle is still America’s weapon of choice.

So what is a lower Receiver?

This is for all the CNN reporters who butcher these simple definitions. The lower receiver of an AR-15 is a more than a part; it is the single piece that every other part revolves around. Modular rifle design developed to adapt to the changing needs of individual soldiers. Lowers are (supposed to be) universal and the parts that go in and on them are interchangeable. Triggers are held in place by cross pins. Parts like stocks, buffer tubes, pistol grips, and selectors all come together to form the fully functional lower.Why buy just a lower?

In today’s market, most people buy lowers with uppers as complete rifles. But we’re looking at a different route and building the guns to our exact wants and needs. As everything revolves around this one piece, we thought we’d show it some love. There are four main ways lowers are sold:- Complete rifles (I know of very few people who make their rifling buying choices based on the design of the lower, but it can happen. LWRC, for example, has a stylized lower that has drawn fans)

- Complete lowers (these have all of the guts intact–trigger, controls, etc. Minimal DIY)

- Stripped lowers (while these are ready to be built, they allow for more customization)

- 80% lowers (for advanced DIY enthusiasts–more on these below)

Buying a complete lower

Buying a complete lower is a great way to go if you don’t have the tools or know-how to assemble your own gun. You can get them from your favorite manufactures. Palmetto State Armory is popular with those looking for reliability at a low price. With endless options and the Internet at your disposal, you can find a lower that is built exactly the way you want it. These lowers can be purchased online and then shipped to your local FFL for transfer on the old 4473 form you would use to buy any gun. If you are looking for some semi-custom choices, but are not ready to dive into amateur gunsmithing, then this path is for you.Buying a stripped lower

What if you want more options? Say you like the looks or feel of one lower, but want a specific design to the trigger shoe on your two-stage trigger, and no one is selling that as part of a package deal? Buy a stripped lower and build it yourself. This is the best way to go if you want to build a rifle with only the best components.It’s also a great way to go if you want to build a rifle on a budget. Stripped lowers can be had for a song–sometimes below $50. As the lower isn’t immune to the whims of firearms fashonistas, they can range into the hundreds of dollars. For your first build, keep it simple. As you learn the ins-and-outs of controls, mag-well shapes, the relative weights of component parts, then you can swap out the simple lower receiver for one that does exactly what you want.

Head my warning though–if you are looking to build a budget gun and don’t have much experience, assembling a lower can be a daunting task. Know your skill level. Remember that these are modular in design, and that parts are supposed to fit. Don’t remove material. Don’t force anything. Gunsmiths aren’t cheap. Check out the options like the DSA pictured above–clean, simple, priced right, and completely customizable.

A quick detour into material construction

While we’ve been looking at the basics of how these are sold, we’ve skipped over an important aspect of design. Most are built from varying grades of aluminum. The material is strong enough, easy to work, doesn’t rust, and light. And if it does break, the part is easy to replace. Yet there’s more to consider.Cast lowers: some lowers are milled out of aluminum that has been melted and poured into a basic mold. While expedient, this method produces a loose crystalline structure within the aluminum. Is it strong enough? Yes. Is is the strongest method? No.

Milled lowers: while most lowers are milled at some point in their construction, some are milled from billets of aluminum. A billet is just bar stock. The strength of the bar itself (which is determine by how it is made) determines the strength of the final product. This method often produces a stronger lower than simple casting.

Forged lowers: if you want something more, look to forged lowers. These are made from billets that are hammered into molds, or compressed under pressure. This forging is then milled. The compression of the crystalline structure makes this one of the strongest methods of construction.

If you are looking at aluminum, consider the end cost. More strength equals more production time. Is it worth it? Maybe. It depends on the intended purpose of the gun. If you want even more strength (or even less) there are other options. What other materials are common? Just about everything.

For those who want an AR to look at, I’d suggest Turnbull’s TAR-15. It is made of steel. That’s kind of like saying the Hope Diamond is made from coal. Turnbull makes some pretty guns. If you’d rather not lug around ferrous metals, you can try carbon fiber. Tegra Arms makes light-weight lowers out of our generation’s space age materials. The one above is a carbon fiber composite, which means the polymer is reinforced with an incredibly light and durable material.

Or maybe you want titanium? You know–why not have a rifle that will outlive you, and your kids, and your kids’ kids…. These will likely have the same service life as a 1950’s Russian AK. Nemo Arms, a company that pushes the limits on the AR pattern rifles, has an AR-10 made from titanium. Why not an AR-15?

Maybe because it is overkill. Plastics work fine. Polymer lowers have been a thing of novelty in the past, but in recent years polymer technology has advanced to a point that the polymer lower is a viable option. These lowers can handle serious use and cost even less than a stripped aluminum lower. Tennessee Arms Company is a leader in this field as they have developed an entire line of polymer lower receivers reinforced with marine grade brass where strength is necessary. These lowers are inexpensive, hold a lifetime warranty, and are about as cool as they get. And some hold the opinion that the plastic lowers flex where aluminum lowers crack.

The

polymer reacts better, we’re told, than some metals. It has more

elasticity, and handles recoil energy without cracking. And the jig

shows what needs to be removed to make it work.

Buying a 80% lower

http://www.80percentarms.com/collections/lower-receiversLowers that are serialized and considered by the ATF to be firearms must be transferred through an FFL, at least originally. What if you want to skip that step? 80% lowers may be the best option. If a lower is only 80% complete, it is not yet a firearm. Therefore, it requires no special paperwork. It can be bought from a manufacturer and sent directly to you.

You finish the last 20%, and make it into a functional lower receiver. How hard is that to do? It takes a bit of skill, but it is hardly an advanced project. If you can operate a drill press and are confident in your ability to measure things correctly, the job is easily accomplished.

They come in polymer, from folks like Polymer80 and in Aluminum from 80percent arms.

Read our reviews of the 80% build processes here:

Once you get a handle on the basics, you may want to mill your own lower. Aluminum is harder to cut than plastic.

The flip side to this coin is that the lower you manufacture is truly your gun. You are the manufacturer. It is un-serialized, and something you can show off to your friends for years to come. Building out a 80% lower does require time and a bit of skill, but if you are reasonably good with power-tools, there is no greater reward than building a gun around a lower receiver you milled yourself.

In the end

Once you’ve decided on how much time and work you want to put into a lower, and what materials you are looking for, you can fine-tune the process. While most lowers are the same basic shape, there are nuances that can be important. Do you want or need a left-handed design? A right hand orientation with ambidextrous controls? Are you looking for a wider mag well to make loading easier? Would you prefer grooves on the front of the mag well for support hand grip? How much decoration do you want on the lower itself? Do you risk sacrificing durability for weight reduction and go with a skeletonized lower that is feather light?The AR-15 is everything it can be because of the lower. There have never been more options than there are today. Find what appeals to you and be honest with yourself on what you are comfortable and capable of taking on.

Advanced Mil-Dot: Estimating Distance Using Your Scope

Recently we introduced the whole concept of the mil-dot (or milliradian) system for rifle scopes in Mil-Dot Made Easy.

In that article, we got into the practical application of how mil-dot

scopes can be used to figure out how to aim at a distant target. With

simple math, you can figure out how much adjustment to make to your

optic to account for bullet drop at longer ranges. The same system can

be used to calculate windage adjustment to account for crosswinds and

figuring out how much to lead a moving target.

That’s all fine and cool, but what I like most about the mil-dot system is that it can be used to figure out the distance to a target, just by looking through your optic. Hey, when the Zombies come, batteries are going to be in short supply, and those fancy laser rangefinders will only work for so long.

In fact, one of the earliest uses of the mil-dot ranging system allowed submarine commanders to figure out how far away an enemy ship was. This knowledge, used with some basic math that factored in the speed of their torpedoes, told them where to aim in order to intersect the path of the ship. If you’re ancient enough (like me) to have played that old arcade game Sea Wolf, you’ll know the concept. Except back then, you had to guess when to launch the torpedo, and it took a lot of quarters to nail the timing consistently. If you don’t know what an “arcade game” is, count me as envious of your youth.

Likewise, mil-dot markings in your scope can easily be used to figure out how far away a person, animal, or object is from your current position. It’s a matter of proportion. For example, have you ever tried to help someone spot a planet in the night sky by telling them something like, “Look two thumb widths over from the moon and you’ll see it?” Obviously, Mercury is somewhat farther than two thumbs away from the moon. Your thumb width is just represents a proportional distance relationship. The width of your thumb two feet from your eyes represents some millions or billions of miles of distance far out in space.

The concept of determining how far away something is using mil-dots is similar. Because the proportional size of an object is constant with distance, you can use some basic algebra principles to figure out the range. Don’t freak out because I used the word “Algebra!” I hated that class too, but there is one important thing we all learned that applies here. Remember “solving for X?” All that really boiled down to was knowing that if there are three pieces of information, and you know two of them, you can usually solve for the missing third one. In this case, you can always solve for the missing piece of info at the relationships are proportional.

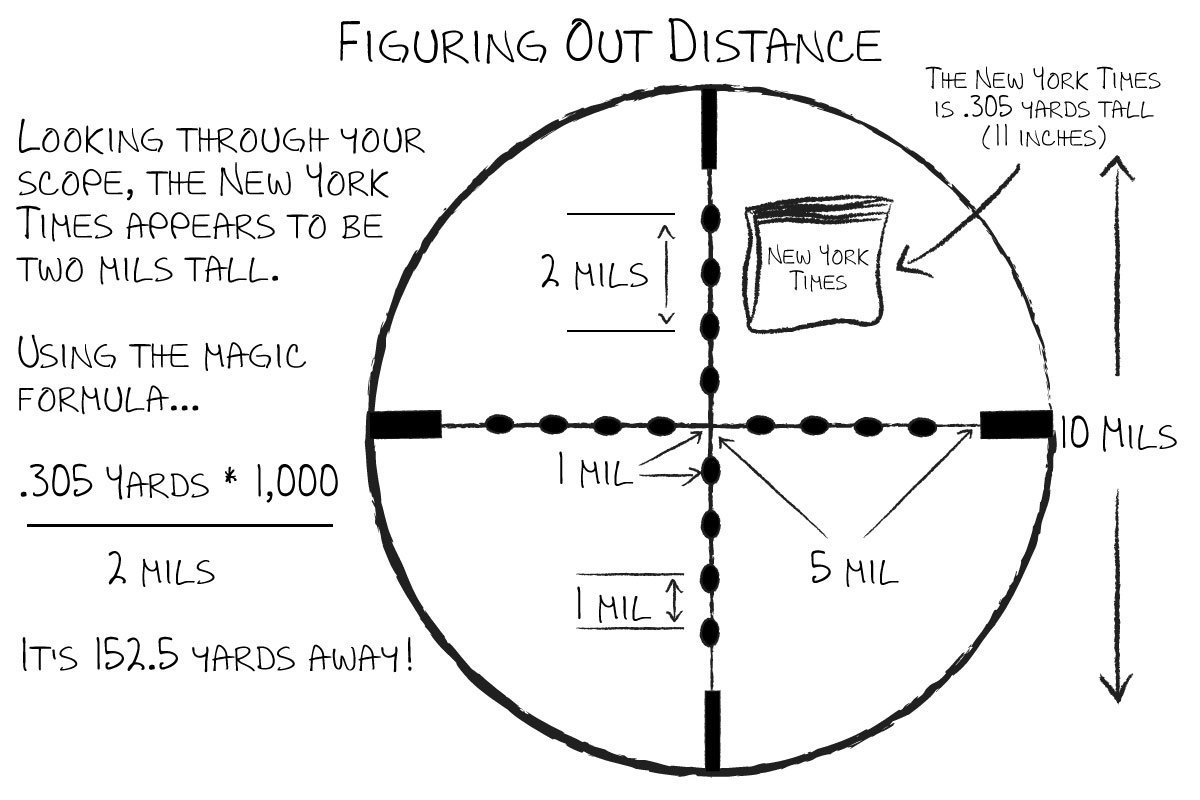

At risk of grossly oversimplifying math and ticking off my 8th-grade algebra teacher, it works like this. With a mil-dot scope, we know that the measurements between dots on the scope reticle equate to 1 yard at 1,000 yards distance. If we also know the actual size of a distant object, like a person standing, fence post, or copy of the New York Times, then we have two pieces of known information. The only thing missing is the distance between our scope and the known size object.

Let’s use a real-world example to illustrate the idea.

Suppose we want to shoot a copy of The New York Times. Yes, that brings me joy, but that story is for another day. Someone has placed it down range at an unknown distance. As hardly anyone knows, the width of The New York Times is about 12 inches. When folded, as it would be in a newspaper rack, it’s about 11 inches tall. Now, if someone put our example entirely objective content newspaper at close range, say 5 feet, it would look pretty big through a scope. However, if they placed it 300 yards down range, it would appear to be a puny little thing, even less worthy of a read than normal. That’s the whole proportion thing in action. They farther away it is, the smaller it appears.

Here’s where the magic of mil-dot comes into play. What if we “measured” the size of our downrange newspaper using the mil-dot markings in the scope? Using the scope marks like a ruler, we can look at the paper through the scope and see how many “mil-dots” in the scope reticle it covers. At close range, say 10 yards, the paper might appear to be 20 mil-dots tall. At long range, it might only be one or two mil-dots tall. Here’s where we can use our two “known” pieces of information to figure out how far away it is. We know the length of a mil-dot at a fixed range of 1,000 yards. We also know that the New York Times, when folded, is about 11 inches tall. The only piece of missing information is the distance between us and the formerly-epic example of investigative journalism.

Here’s where the proportions come into play. Remember from the previous discussion that one milliradian (mil) equates to one yard at a distance of 1,000 yards. For illustration’s sake, imagine standing a yardstick upright 1,000 yards down range. When we look at that through a mil-dot scope reticle, it will appear to be exactly one mil tall.

That’s the basis of the proportion relationship. If a one-yard tall object appears to be one mil tall through the scope, it must be 1,000 yards away. If it appears to be two mils tall, then it’s only 500 yards away. If the object is not exactly one yard tall, then you need to adjust accordingly.

Let’s say that The New York Times appears to be two mils tall through our scope. But we know that it’s only .305 yards tall. We also know that a one-yard tall object that appears to be two mils tall through the scope is 500 yards away, so a smaller object that appears two mils tall must be closer, since it appears larger.

Rather than get all wrapped up in the words, there’s a simple formula to figure out the range. It relies on knowing the actual size of the object your are ranging and the number of mils that it appears to be through your scope.

Plugging these values into the formula, we get:

The same formula works with meters too, as long as you’re consistent.

It sounds complicated, but once you get the hang of it, you can use this system almost anywhere, because there are almost always objects of known size nearby. For example:

That’s all fine and cool, but what I like most about the mil-dot system is that it can be used to figure out the distance to a target, just by looking through your optic. Hey, when the Zombies come, batteries are going to be in short supply, and those fancy laser rangefinders will only work for so long.

In fact, one of the earliest uses of the mil-dot ranging system allowed submarine commanders to figure out how far away an enemy ship was. This knowledge, used with some basic math that factored in the speed of their torpedoes, told them where to aim in order to intersect the path of the ship. If you’re ancient enough (like me) to have played that old arcade game Sea Wolf, you’ll know the concept. Except back then, you had to guess when to launch the torpedo, and it took a lot of quarters to nail the timing consistently. If you don’t know what an “arcade game” is, count me as envious of your youth.

Likewise, mil-dot markings in your scope can easily be used to figure out how far away a person, animal, or object is from your current position. It’s a matter of proportion. For example, have you ever tried to help someone spot a planet in the night sky by telling them something like, “Look two thumb widths over from the moon and you’ll see it?” Obviously, Mercury is somewhat farther than two thumbs away from the moon. Your thumb width is just represents a proportional distance relationship. The width of your thumb two feet from your eyes represents some millions or billions of miles of distance far out in space.

The concept of determining how far away something is using mil-dots is similar. Because the proportional size of an object is constant with distance, you can use some basic algebra principles to figure out the range. Don’t freak out because I used the word “Algebra!” I hated that class too, but there is one important thing we all learned that applies here. Remember “solving for X?” All that really boiled down to was knowing that if there are three pieces of information, and you know two of them, you can usually solve for the missing third one. In this case, you can always solve for the missing piece of info at the relationships are proportional.

At risk of grossly oversimplifying math and ticking off my 8th-grade algebra teacher, it works like this. With a mil-dot scope, we know that the measurements between dots on the scope reticle equate to 1 yard at 1,000 yards distance. If we also know the actual size of a distant object, like a person standing, fence post, or copy of the New York Times, then we have two pieces of known information. The only thing missing is the distance between our scope and the known size object.

Let’s use a real-world example to illustrate the idea.

Suppose we want to shoot a copy of The New York Times. Yes, that brings me joy, but that story is for another day. Someone has placed it down range at an unknown distance. As hardly anyone knows, the width of The New York Times is about 12 inches. When folded, as it would be in a newspaper rack, it’s about 11 inches tall. Now, if someone put our example entirely objective content newspaper at close range, say 5 feet, it would look pretty big through a scope. However, if they placed it 300 yards down range, it would appear to be a puny little thing, even less worthy of a read than normal. That’s the whole proportion thing in action. They farther away it is, the smaller it appears.

Here’s where the magic of mil-dot comes into play. What if we “measured” the size of our downrange newspaper using the mil-dot markings in the scope? Using the scope marks like a ruler, we can look at the paper through the scope and see how many “mil-dots” in the scope reticle it covers. At close range, say 10 yards, the paper might appear to be 20 mil-dots tall. At long range, it might only be one or two mil-dots tall. Here’s where we can use our two “known” pieces of information to figure out how far away it is. We know the length of a mil-dot at a fixed range of 1,000 yards. We also know that the New York Times, when folded, is about 11 inches tall. The only piece of missing information is the distance between us and the formerly-epic example of investigative journalism.

Here’s where the proportions come into play. Remember from the previous discussion that one milliradian (mil) equates to one yard at a distance of 1,000 yards. For illustration’s sake, imagine standing a yardstick upright 1,000 yards down range. When we look at that through a mil-dot scope reticle, it will appear to be exactly one mil tall.

That’s the basis of the proportion relationship. If a one-yard tall object appears to be one mil tall through the scope, it must be 1,000 yards away. If it appears to be two mils tall, then it’s only 500 yards away. If the object is not exactly one yard tall, then you need to adjust accordingly.

Let’s say that The New York Times appears to be two mils tall through our scope. But we know that it’s only .305 yards tall. We also know that a one-yard tall object that appears to be two mils tall through the scope is 500 yards away, so a smaller object that appears two mils tall must be closer, since it appears larger.

Rather than get all wrapped up in the words, there’s a simple formula to figure out the range. It relies on knowing the actual size of the object your are ranging and the number of mils that it appears to be through your scope.

Plugging these values into the formula, we get:

The same formula works with meters too, as long as you’re consistent.

It sounds complicated, but once you get the hang of it, you can use this system almost anywhere, because there are almost always objects of known size nearby. For example:

- The average fencepost is about 4 feet (1.33 yards) tall.

- An “average” man standing is 70 inches (1.94 yards) tall.

- An average man sitting is 33 inches (.917 yards) high.

- A Russian T-72 Tank is about 1 yard from the ground to the base of the turret. OK, maybe we don’t all know the tread height of a T-72, but you have to admit, it’s an interesting factoid to file away. I didn’t know it either, and had to look it up.

The 100% American Made AK: The Ras-47

Visit the Century site: http://www.centuryarms.com/

Made in America

Recently, American consumers have been clamoring for American-made goods. From baby toys to dog food, few things have escaped the ire of these patriotic purchasers. Once exception is Mikhail Kalashnikov’s namesake, the AK-47. For years AK elitists have considered anything not made behind the Iron Curtain to be cut rate; and in many cases they’re correct. However, Century Arms, the largest importer of AKM carbines, has decided in light of recent importation sanctions to shatter the myth with their own all-American AKM, the RAS-47. How does it stack up against decades of AK-manufacturing experience of overseas builders? Better than anyone could have guessed.Though it begs the question why. Why would Century undergo the tremendous cost, time and effort to produce a 100 percent American-made AK when countless countries fielded hundreds of millions of the rifles that can be parts kitted out, saving them millions of dollar?

In a word, sanctions. In two: import restrictions.

In response to the aggressive military actions of Russian prime minister Vladimir Putin, President Obama issued punitive economic sanctions against them. One of these actions was the restriction on imports of Russian-made firearms into the United States. While some manufacturers were spared, the largest Russian manufacturer of AK rifles, Izhmash, was not. This lead to increased fear that all AK rifles would face importation restrictions VIA executive order. This, combined with the huge time delay on imported firearms stuck in US Customs and so-called sporting clause limitations caused by section 922r, created an unstable AK resource market.

Rather than be subject the whims of a notoriously anti-firearms president or the trepedacious nature of hawkish Eastern European oligarchies and their country’s seemingly nebulous borders, Century decided to create their own parts source market.

RED ARMY STANDARD (RAS) 47 Semi-Auto Rifle

- Caliber: 7.62x39mm

- Capacity: 30 rds.

- Receiver: Stamped

- Barrel: 16.5″ with a 1:10 twist, 14×1 LH

- Overall: 37.25″

- Weight: 7.8 lbs

A note on Century

Before we continue, it’s important to address the concerns of gun forum-goers everywhere. Yes, Century Arms made some mistakes in the past with their builds. Given the volume of their products, this is unavoidable. Also, given the company’s prolific nature, the reports of these issues are often overstated. How many times do shooters buy a gun from any maker, and excitedly post online that it runs as advertised?Additionally, the majority of issues with Century’s most problematic rifle, the Romanian WASR, had nothing to do with Century’s mechanical or manufacturing capabilities. Since the most prominent issue were canted iron sights and these are a result of poor build quality by the Romanian armory where they were made. In that case, the alterations Century made had nothing to do with the front sight. Still, there’s no denying that Century should have caught these issues with their quality assurance team.

Previously Century was known as the economical (read: cheap) way to get into the AK game. Their new approach centers on building the best, without having a cost-prohibitive price point. Though their approach is sure to aggravate purists and collectors alike.

The

iron sights on most all AKs are basic, at best. While the RAS-47 is no

different, the sights are appropriately durable. And the barrel is

threaded, too. Bonus.

The new Century?

Instead of simply checking off every box on an AKM build checklist for what it takes to make a mil-spec AK, the new RAS-47 seeks to surpass it. While many of said improvements are obvious upgrades, some of the areas where Century made alterations offer questionable benefits. Such as the lightening cuts made to the bolt carrier to reduce lockup time and the omissions on the bayonet lug. Neither of these bother the overwhelming majority of prospective buyers, but the remaining five percent malcontents are disproportionately vocal. Other deviations include the lower handguard interface which is made to Russian standards, so Romanian-type furniture will require minor fitting, and the addition of their own proprietary polymer, finger-grooved pistol grip. The latter of which is precisely what Century ships on their N-PAP series of rifles – though more traditional replacements can be purchased online for as little as $10.Which is great, because personally, I detest grooved pistol grips. This is because these grips are meant for someone who perfectly fits them. Nine times out of ten, I’m not that guy. While less of an issue with Hogue rubber grips that have some give, these hard plastic grips are pretty uncomfortable especially when holding the rifle with one hand during tactical reloads. That said, many of my larger-handed compadres found the Century grip to be much more comfortable than factory ones. The best solution would be to try and handle one yourself before buying, but again it’s only a $10 fix if a shooter determines they aren’t correct for them. Though this isn’t the only furniture option available on the carbine.

Shooters have their pick of the more traditional wood-stocked version or the tactical Magpul one. The Magpul version features the wildly popular new series of polymer AK furniture announced just prior to SHOT Show 2015. The handguard of which features Magpul’s proprietary accessory-mounting system known as M-Lok. This is great news for both tactical gear-lovers and pragmatists alike since most other mounting options add considerable weight forward of the magazine well. Anyone who has ever carried an AK or fired one extensively can attest that the gun is sufficiently weighty as it comes, and the added forward weight shifts the balance towards the muzzle, making the carbine feel sluggish and needless heavy.

Shooting the RAS-47

All

groups in the data below were fired from the prone position and are

5-round groups achieved at 100 yards. Each shot was taken approx 10

seconds apart to allow proper barrel cooling. Loads were measured 10

feet from muzzle with RCBS AmmoMaster Chronograph and are the rounded

average of 3 five-shot groups.

Though it’s what’s beneath this handguards that really sets the

Century RAS-47 apart from competitors. Whereas military specification AK

carbines feature a chrome-lined steel barrel to better resist

corrosion, Century’s new carbine uses a stainless barrel coated in black

nitride. The result is a remarkably accurate rifle that defies the AK’s

reputation as a crudely-made, inaccurate leadslinger. In testing, the

RAS-47 proved more accurate than many off-the-shelves AR-15 carbines;

achieving five-round groups just over one MOA at 100 yards with Hornady

SST ammunition–a feat I deemed impossible for the platform prior to

shooting this rifle.- Red Army Copper-jacketed 123gr FMJ–1.74″ – 2411 FPS

- Hornady 123gr SST–1.12″ – 2306 FPS

- Prvi Partisan 123gr FMJ–1.91″ – 2403 FPS

- Silverbear 125gr SP–2.24″ – 2367 FPS

- Tulammo 123gr FMJ–1.44″ – 2321 FPS

A

decent mount will allow you to use precision optics to their full

potential. This is a Hi-Lux 1-4x24mm CMR-AK762 mounted in a Midwest

Industries 30MM AK Side Mount (barely shown).

Both offer great mounts that were utilized in this review, and drastically increased the carbine’s usability, while assisting it in reaching its potential. This is especially true when paired with a high-quality magnified optic; shooters can’t hit what they can’t see.

Below this mount is another non-traditional addition to the AKM, an extended magazine release – Though referring to it as such is misleading. The release isn’t simply extended, but also widened so shooters can more easily release empty magazines. In testing, this upgrade offered little time savings to more experienced AK-runners, but newer shooters appreciated the wider controls. In my experience they are greatly helpful for shooters using alternative reloading techniques, such as dislodging the spent magazine with the middle finger of the firing hand, without leaving the pistol grip. Not simply because it’s easier to reach, but also because the extended portion offers greater mechanical advantage, thus reducing the amount of force required to do so. Again, mostly unimportant for traditional shooters, but those running an AK under the clock will appreciate the precious milliseconds saved.

Even though the RAS-47 has a myriad of atypical features for an AK, it still retains many iconoclastic details that function well and maintain the traditional AK aesthetic. For instance, unlike Century’s first attempt at an domestic AK clone, the C39, the RAS-47 uses a standard AKM post and notch iron sights. The rear leaf sight is adjustable for drop and has pre-measured distances notched out for rapid target engagement.

Another classic feature is the slant muzzle brake topping the RAS-47’s barrel. It features AKM-standard 14X1mm LH threading, so shooters can purchase alternatives designed to fit any AKM carbine that doesn’t use the larger mount on AK-74 or AK-100 series rifles. Although this addition is aesthetically pleasing and functional, I feel Century would have been better served introducing their own brake, but only if it wouldn’t have affected the rifle’s price point.

Prices range from $669.99 to $859.99 depending on furniture. This model regularly sells for less than $600. Given the high price of the optional Magpul furniture, shooters are getting what they pay for in both instances. So whether a shooter is looking for their first AK rifle, a remarkable accurate carbine in an inexpensive caliber or simply an attractive, ultra-reliable plinker – the Century Arms RAS-47 won’t disappoint.

Ammunition for for this review provided by Hornady Manufacturing and Century Arms.

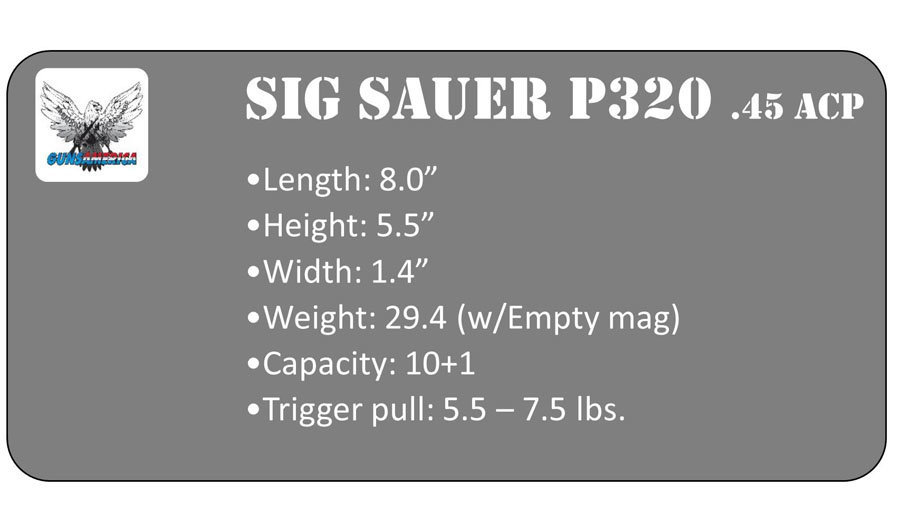

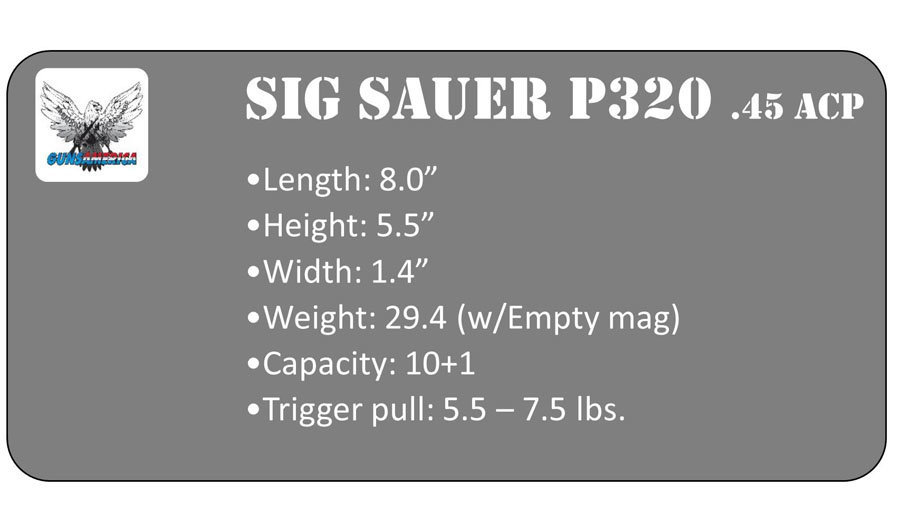

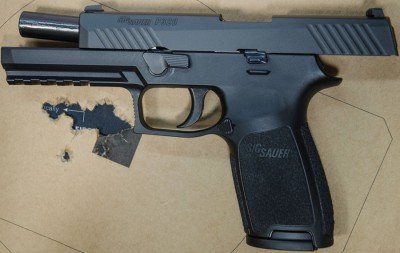

SIG SAUER P320 Grows up – to .45 ACP (Review)

Check out the SIG P320: http://www.sigsauer.com/CatalogProductDetails/p320-full.aspx

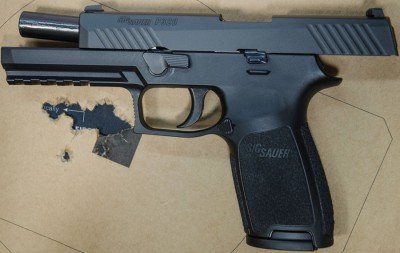

When the SIG SAUER P320 was introduced, it was met with cautious optimism. After all, the P250 platform that first introduced the polymer framed, modular component concept at SIG didn’t exactly set the world on fire. But then few innovations really do take off on their first flight. The Wright brothers made several piles of scrap in their field before making history. The P320 is a striker-fired, rather than hammer-fired platform that uses an internal chassis or fire control group as the serialized gun (SIG calls this the “frame” to make things really confusing) – everything else is just “parts” and not a firearm. If this is all old news to you, then you’ve seen it before. The P320 series has been out for a while now – about a year. But not in .45 ACP – until now. Initially expected in the early spring of 2015, it has been slow in coming for those of us who love the P320 and love 230 grain projectiles.

I do admit without shame that I am a fan of the Sig Sauer P320. The consistency of the platform is very impressive, as is the ability to quickly re-purpose your firearm from a subcompact 9mm to a full sized .40 or .357 Sig in mere seconds. It’s like Transformers for gun geeks! But I remember thinking, as I lifted the first 9mm P320 that I fired, “boy, I really wish this was a .45!”. I don’t know why it is, among many gun-folk, that a handgun somehow becomes more legitimized when offered in .45 ACP. But as long as I’m confessing, I will also admit that I buy into it too.

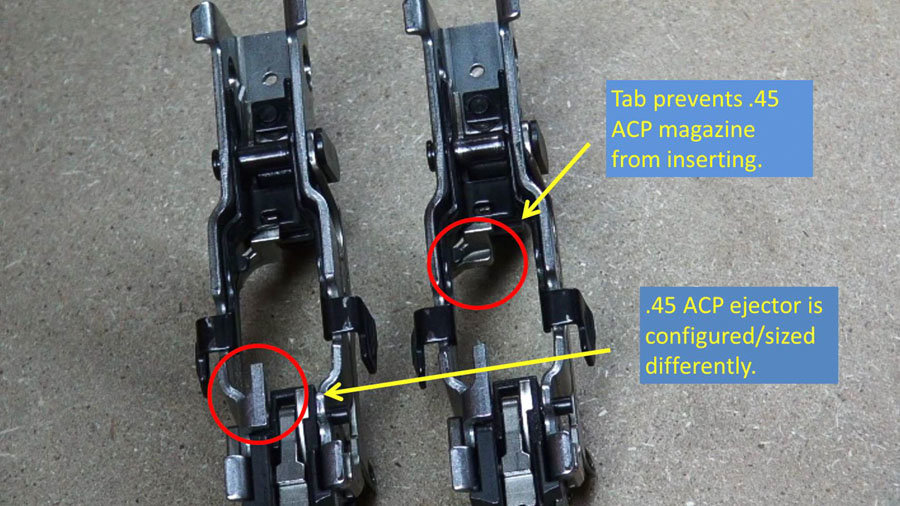

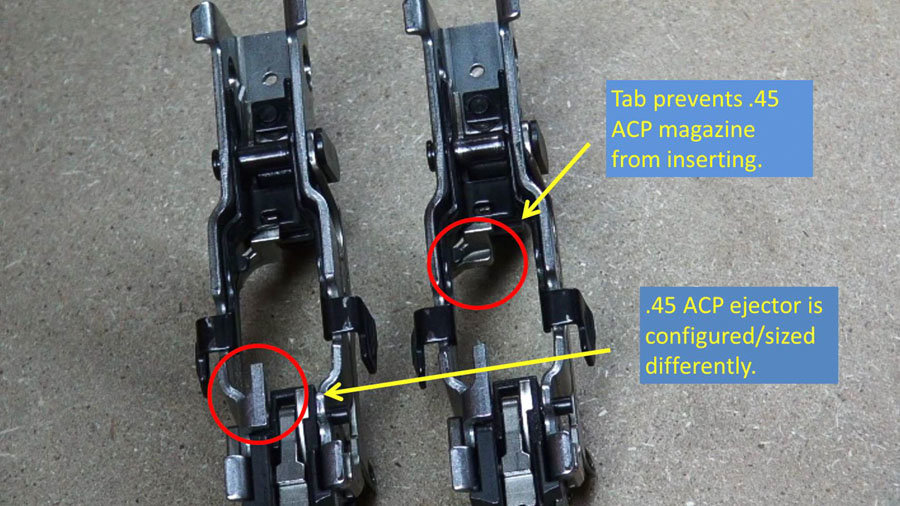

The first thing I did when I got the P320 .45 on my work bench was pull a 9mm version apart and try mixing parts. Everything looks promising at first – but they do not interchange. The reasons, as I’m able to observe, are two: First and foremost it is a magazine size issue. 9mm, .40 S&W, and .357 Sig can all fit into a magazine of identical box dimensions. The .45 ACP cannot. The box of the .45 magazine is both wider and deeper to accommodate the bulky cartridge, and therefore requires a specially molded grip module. Reason two is the ejector.

The only functional difference I could see between the smaller

caliber chassis and the .45 chassis is the fact that the latter uses a

shorter ejector. Not surprising, once I realized it. I have no doubt

that there would be malfunctions if that were not so. The chassis for

non-.45 calibers also includes a metal tab to prevent the .45 magazine

from being loaded in. For all intents and purposes then, the .45 Auto

variety of the P320 family stands alone. There is still the good news

that you can eventually have several sizes (four, if they follow the

Full, Compact, Carry, and Subcompact offerings) in .45 ACP that use just

one serialized chassis.

Like its smaller caliber siblings, the P320 .45 comes with two magazines and a convenient (and actually quite good) polymer paddle holster. The full sized magazine for the full sized grip panel (what we would call the ‘frame’ of any other pistol) holds 10 rounds. This puts it on par with the majority of .45 autos, but comes up short of several models offered by Glock, Springfield Armory, and others. Never is the “Size vs. Capacity” argument so relevant as with the massive .45 Auto cartridge. I don’t mind 10+1 and I think it allows for a “just right” sized pistol stock.

My copy of the P320 came equipped with the optional SIGLITE® night

sights. The standard sights are 3-dot contrast. That is the only

optional choice with the P320 line, except for some marketing driven

color options for the grip modules such as flat dark earth (FDE). Night

sights raise the price of the gun, but the various color offerings

generally do not. Fit and finish is typical Sig Sauer. In other words,

excellent. One may be tempted to poo-poo the look and feel of the dull

poly lower on these guns, but remember – Sig does not consider these a

permanent part of your firearm and replacements are $46 as of this

writing.

That said, the design of the grip module is fantastic from an ergonomics and practical perspective. The look is pure Sig, and your hand feels right at home wrapped around it. The grips are available in three hand sizes for each module size for each caliber. Scratching your head yet? Okay, it works like this: For each caliber offered, the P320 is (or will be) available in Full size, Compact, Carry, and Subcompact. Then, each of those sizes can be had in small, medium, or large. That’s twelve permutations of each caliber P320! And that’s not considering the fancy colors like FDE. Essentially, the S,M,L sizing changes only the circumference and reach aspects of the grip surface, making them thinner or thicker in the handle. The length and height don’t change. Each grip module has molded-in grip texture that is very akin to the modern E2 style grips on newer Sig pistols. I like this texture and find it very effective.

What made me fall in love with the P320 though, was the trigger. I

was pleased to see that Sig did not follow the crowd when it comes to

striker-fired triggers, but instead made the P320’s bang switch out of

steel and left it smooth faced and thick. It has a Sig shape and feel.

But most of all what it has is an incredibly crisp break and reset. I

was hoping that the .45 version would be just as good as the 9mm and .40

that I’m accustomed to. Sig specs the trigger pull at between 5.5 and

7.5 lbs. My measured average tipped the scale at just under 7 lbs. But I

have often opined that the weight of the trigger is far less important

to a good shooting experience than the cleanness of travel and crispness

of break. And because both those elements are superb on the P320, the

feel of the trigger is much lighter than those numbers suggest.

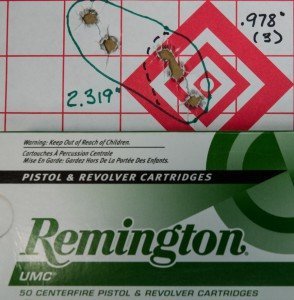

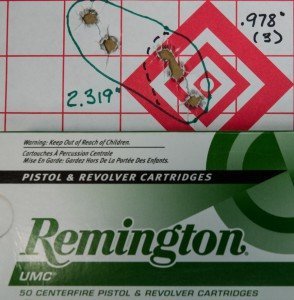

Sig Sauer supplies the P320 pistols with two magazines and a polymer paddle holster. Before you scoff at the “free holster”, I’ll tell you that it’s a pretty good one. Of course it fits your new Sig perfectly, and it’s sturdy and very practical. I’d be happy to wear it out before I felt the need for a new one – even if this were to be a competition gun. The magazines hold 10 rounds, and are manufactured by Mec-Gar in Italy. They functioned flawlessly in all my testing – as did the pistol. Not a single malfunction of any kind after nearly a half-case of Remington UMC, some Winchester, Federal, Freedom Munitions, and steel cased Tul Ammo. I even fed it a whole box of my handloads for good measure. Everything feeds, fires, and ejects without a hitch.

I did some 25-yard accuracy tests, rested on a bag. The results were good overall, with a pretty wide spread between best and worst. The P320 seemed to like the Remington UMC the best, followed closely by Winchester white box.

Looks like we’ve got a blue collar gun here that likes to shoot what you can find at the local discount store. I shot five-shot groups, and then from those I also chose a “Best Three” subgroup. The best performance was a three shot group from Remington at just under 1 inch.

Controls are sparse, well placed, and function very well. The slide

stop/release levers appear on both sides of the pistol for all P320’s.

It’s not as high quality as you may be accustomed to on a Sig, but it’s

part of the removable chassis and had to be designed for universal fit.

Easy to reach without altering one’s grip, it operates just fine. The

triangular and aggressively grooved magazine release is one of the best

I’ve used. The button is large and easy to depress. You don’t feel like

there is an automobile suspension spring behind it. Magazine ejection is

clean, fast, and very positive. The control is reversible for lefties.

The only remaining control you’ll find out the outside of the pistol is

the one that bugs me. It’s the takedown lever, and in my opinion it is

far too large – mainly in the thickness department. It adds about 1/8”

to the thickness of the pistol. Not a big deal maybe on the full sized

frame – but a very big deal on a subcompact. The takedown lever is part

of the serialized chassis – and moves with it from module to module if

you buy kits. It also interferes with the thumbs forward shooting grip –

sitting right where your thumb wants to be. Sure, I can move my thumb

under it, and I do (or it takes a beating), but I have to think about it

every time I grip the pistol. Maybe there is an engineering reason for

the mass of this lever, but if not I would like to see that thing put on

a serious diet. Someone at Sig needs to talk to someone at Springfield

Armory – they’ve got this figured out.

The trigger guard is square and large with serrations on its flat front for those who use that as a finger-hold. The magazine fits flush to the grip frame and does not protrude on any side. There is a tabbed area on either side of the grip to allow grabbing and assisting the magazine’s exit, should that ever be necessary. The grip is finished off with a lanyard ring at the heel.

The entire line of P320’s is just a year old, and the .45 ACP is

still so new that Sig Sauer still lists it as “coming soon” on their

website. How it will fare over the long haul is still a question to be

answered. Whether or not LE agencies will adopt it as a duty gun or full

service platform remains to be seen. But as I said up front, I’m a fan

of the design concept and I think can become a proven warrior. Where I

think Sig stands to hurt itself with the P320 line is in the accessories

and kits department. Exchange kits are still hard to obtain, and Sig

has recently raised the price of them significantly (about one third!).

If you cannot get a grip module or caliber conversion you want, or have

to pay nearly the price of a whole new pistol for it, there isn’t a lot

of value in the concept. Let’s hope that they find a price point that

works for them and us – and that they fill the shelves soon.

When the SIG SAUER P320 was introduced, it was met with cautious optimism. After all, the P250 platform that first introduced the polymer framed, modular component concept at SIG didn’t exactly set the world on fire. But then few innovations really do take off on their first flight. The Wright brothers made several piles of scrap in their field before making history. The P320 is a striker-fired, rather than hammer-fired platform that uses an internal chassis or fire control group as the serialized gun (SIG calls this the “frame” to make things really confusing) – everything else is just “parts” and not a firearm. If this is all old news to you, then you’ve seen it before. The P320 series has been out for a while now – about a year. But not in .45 ACP – until now. Initially expected in the early spring of 2015, it has been slow in coming for those of us who love the P320 and love 230 grain projectiles.

I do admit without shame that I am a fan of the Sig Sauer P320. The consistency of the platform is very impressive, as is the ability to quickly re-purpose your firearm from a subcompact 9mm to a full sized .40 or .357 Sig in mere seconds. It’s like Transformers for gun geeks! But I remember thinking, as I lifted the first 9mm P320 that I fired, “boy, I really wish this was a .45!”. I don’t know why it is, among many gun-folk, that a handgun somehow becomes more legitimized when offered in .45 ACP. But as long as I’m confessing, I will also admit that I buy into it too.

One reason .45 ACP is not a mix-and-match with other calibers is the magazine size, and magwell difference.

Modularity and Compatibility

And then there is the issue of compatibility with other P320’s. It’s not. So let’s start right off with the disappointing part. By compatible I mean the ability to remove the chassis from a .45 and insert it into the kit (grip frame, side, barrel, etc.) of a 9mm, .40 S&W, or .357 Sig. With no official information that I could find, I was left scratching my head as to why that might be – and more importantly, why Sig would devalue the product line that way. After all, the pressures of the .40 and .357 are greater than the .45… so maybe it was a cartridge diameter issue.The first thing I did when I got the P320 .45 on my work bench was pull a 9mm version apart and try mixing parts. Everything looks promising at first – but they do not interchange. The reasons, as I’m able to observe, are two: First and foremost it is a magazine size issue. 9mm, .40 S&W, and .357 Sig can all fit into a magazine of identical box dimensions. The .45 ACP cannot. The box of the .45 magazine is both wider and deeper to accommodate the bulky cartridge, and therefore requires a specially molded grip module. Reason two is the ejector.

The

other reason is the ejector size and geometry, which is unique for the

.45. A preventative tab is present on the smaller calibers to prevent

use with .45 Auto.

Like its smaller caliber siblings, the P320 .45 comes with two magazines and a convenient (and actually quite good) polymer paddle holster. The full sized magazine for the full sized grip panel (what we would call the ‘frame’ of any other pistol) holds 10 rounds. This puts it on par with the majority of .45 autos, but comes up short of several models offered by Glock, Springfield Armory, and others. Never is the “Size vs. Capacity” argument so relevant as with the massive .45 Auto cartridge. I don’t mind 10+1 and I think it allows for a “just right” sized pistol stock.

Grip

frames are a replaceable commodity with the P320. This is the full

size, medium grip. With five grooves of picatinny rail out front and E2

style texture, it provides a stable base for the gun.

That said, the design of the grip module is fantastic from an ergonomics and practical perspective. The look is pure Sig, and your hand feels right at home wrapped around it. The grips are available in three hand sizes for each module size for each caliber. Scratching your head yet? Okay, it works like this: For each caliber offered, the P320 is (or will be) available in Full size, Compact, Carry, and Subcompact. Then, each of those sizes can be had in small, medium, or large. That’s twelve permutations of each caliber P320! And that’s not considering the fancy colors like FDE. Essentially, the S,M,L sizing changes only the circumference and reach aspects of the grip surface, making them thinner or thicker in the handle. The length and height don’t change. Each grip module has molded-in grip texture that is very akin to the modern E2 style grips on newer Sig pistols. I like this texture and find it very effective.

The trigger on the P320s is pure SIG SAUER. No compromises here.

Sig Sauer supplies the P320 pistols with two magazines and a polymer paddle holster. Before you scoff at the “free holster”, I’ll tell you that it’s a pretty good one. Of course it fits your new Sig perfectly, and it’s sturdy and very practical. I’d be happy to wear it out before I felt the need for a new one – even if this were to be a competition gun. The magazines hold 10 rounds, and are manufactured by Mec-Gar in Italy. They functioned flawlessly in all my testing – as did the pistol. Not a single malfunction of any kind after nearly a half-case of Remington UMC, some Winchester, Federal, Freedom Munitions, and steel cased Tul Ammo. I even fed it a whole box of my handloads for good measure. Everything feeds, fires, and ejects without a hitch.

Sig Sauer P320 .45 ACP Fullsize

The P320/.45 was put through its paces with several types of ammo.

| 25 Yard Results – Rested | |||

| Ammunition Brand | Ammunition Type | 5-Shot Group | 3-Shot Group |

| Winchester White Box | 230 gr. FMJ | 2.382 | 1.050 |

| Remington UMC | 230 gr. FMJ | 2.319 | 0.978 |

| Federal American Eagle | 230 gr. FMJ | 4.535 | 1.997 |

| Freedom Munitions | 230 gr. FMJ | 4.113 | 2.082 |

| TulAmmo | 230 gr. FMJ | 4.264 | 1.660 |

I did some 25-yard accuracy tests, rested on a bag. The results were good overall, with a pretty wide spread between best and worst. The P320 seemed to like the Remington UMC the best, followed closely by Winchester white box.

Looks like we’ve got a blue collar gun here that likes to shoot what you can find at the local discount store. I shot five-shot groups, and then from those I also chose a “Best Three” subgroup. The best performance was a three shot group from Remington at just under 1 inch.

Just edging out the Winchester, the best groups were achieved with Remington UMC 230 grain ball.

The SIG SAUER P320 takes its design inspiration from the X-Five line, making it one sharp looking handgun.

Most P320s ship with the Medium sized grip module, but are available in Large and Small too.

Form and Function

If you like Sigs, you’ll find the feel of this gun in your hand to be a familiar one. Yet, though both are double-stack .45’s, it is thinner than the Sig Sauer P227 because it is a one-piece molded grip body that needn’t be any larger than necessary. On this molded grip, Sig has placed texturing very nearly identical to the E2 grips on their new handguns. I like this texture and feel it does a great job of providing superior grip without the discomfort of some more aggressive styles. You’ll understand just how good that grip texture is, when you see the skin embedded in it after a shooting session. I hear it’s great for removing callouses, too. The beavertail on the P320 full sized frame is a generous one. It gives the web of the hand a comfortable and secure place to wedge itself and aids in the stability of the pistol during recoil. Opposite that is a nicely undercut trigger guard. My smallish hands find the reach to the trigger to be just about ideal with the medium module (which is the most common one shipped for stock orders).

The author’s only pet peeve with the P320 is the over-sized takedown lever.

The trigger guard is square and large with serrations on its flat front for those who use that as a finger-hold. The magazine fits flush to the grip frame and does not protrude on any side. There is a tabbed area on either side of the grip to allow grabbing and assisting the magazine’s exit, should that ever be necessary. The grip is finished off with a lanyard ring at the heel.

Magazine

fit is perfection. Perfectly flush on every side with finger tabs in

the unlikely event that assisted removal is necessary.

The Gun Parts

The important parts of the P320, aside from the removable chassis (or FCU) are all up top. The slide is stainless steel coated with Sig’s impervious Nitron® finish. The 4.7” barrel is typical Sig Sauer and its coating is nearly impossible to mar or scratch with normal use. It sits atop a dual captured recoil spring and guide rod assembly made of steel. A nicely milled and polished breech face and short external extractor finish it off. Taking its design cues from the X-Five series of pistols, the side presents a ruggedly beautiful aesthetic, with its geometric angles and cuts, and large forward serrations.

Every

field strip can easily be a detail strip by removing the FCU. It adds

only seconds to the process and allows you to inspect and clean every

part.

Removable serialized chassis/frame/FCU = gun (top). Gun-shaped polymer parts and slide assembly – not a gun.

Tritium

powered SIGLITE ® night sights are optional, but are among the best

factory-installed night sights because they also provide great daytime

visibility.

The trigger might measure a tad on the heavy side, but it’s so smooth and crisp that you won’t believe the numbers.

It’s nice to see that full-sized bore on a full-sized gun!

The author got almost all of these 20 rounds in one ragged hole at 10 yards offhand.

The included paddle holster is not just ‘okay’, it’s quite good.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)