(Note: I am not an attorney and this does not constitute legal

advice. You’ll find resources in the article to which you can refer for

legal guidance.)

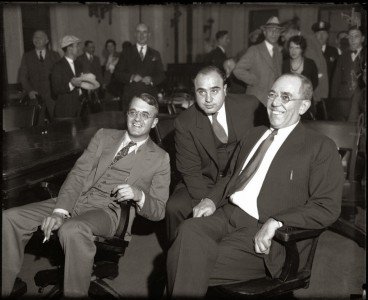

The misunderstandings about the National Firearms Act (NFA) go back a long way. All the way to Prohibition, in fact, to gang warfare and shootings like the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre:

It was February 14th, 1929. The Irish gangster Bugsy Moran, one of Al Capone’s fiercest enemies, ran his bootlegging operation out of a garage on the north side of Chicago. Men dressed as policemen entered the garage and told the seven men they found there that they were under arrest. The men were then lined up in front of a brick wall and unceremoniously gunned down. Al Capone was conveniently at his home in Florida at the time.

The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre was followed four years later, February 15th, 1933, by an assassination attempt on President Roosevelt by Giuseppe Zangara in Miami. Roosevelt escaped unharmed but the mayor of Chicago, Anton Cermak, died from his wounds. The people had had enough.

The NFA was updated through Title II of the Gun Control Act (GCA) of 1968, and the misnamed Firearm Owner’s Protection Act (FOPA) of 1986. FOPA made it illegal for anyone other than the military and law enforcement to possess a machinegun except for those already registered prior to May 19, 1986. It also made components of NFA Firearms, like silencer parts and fully automatic trigger packs, into NFA Firearms under the law. It was justified as an “intent to build” an NFA Firearm.

http://www.auto-ordnance.com/Firearms/Thompson-T1.asp

http://www.auto-ordnance.com/Firearms/Thompson-T1.asp

The process is fairly simple if time consuming. As an individual, you must obtain approval from the ATF, obtain a signature from the Chief Law Enforcement Officer (CLEO) who is the county sheriff or city or town chief of police (not necessarily permission), pass an extensive background check to include submitting a photograph and fingerprints, fully register the firearm, receive ATF written permission before moving the firearm across state lines, and pay a tax. The request to transfer ownership of an NFA item is made on an ATF Form 4. (https://www.atf.gov/file/61546/download)

An alternate method of registering an NFA Firearm is as a corporation, trust, or other legal entity. When the paperwork to request transfer of an NFA item is initiated by an officer of a corporation, a signature from local law enforcement is not required, and fingerprint cards and photographs do not need to be submitted with the transfer request. Therefore, an individual who lives in a location where the chief law enforcement officer will not sign a transfer form, for example, can still own an NFA item if he or she owns a corporation or trust. This method has downsides, since it’s the corporation (and not the principal) that owns the firearm. Thus, if the corporation ever dissolves, it must transfer its NFA to the owners. This event would be considered a new transfer and would be subject to a new transfer tax.

When buying your first silencer or sound suppressor (the terms are used interchangeably), I recommend the Silencer Shop . I have no affiliation with them but they simplified the process for me when I bought my first silencer. They will take you by the hand and lead you through the steps. They also have forms and can help you set up a trust if you decide to go that route. Very responsive and professional group of people.

You can also get forms and instructions through the ATF website: https://www.atf.gov/resource-center/forms-library, and online through sites like https://www.guntrustlawyer.com/form4.

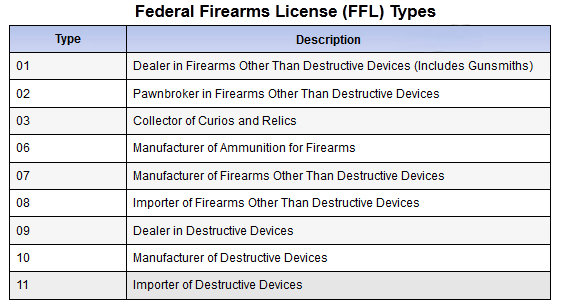

You do not need a “Class III FFL” or any other license. An FFL is required as a prerequisite to become a Special Occupation Taxpayer (SOT): Class 1 importer, Class 2 manufacturer-dealer or Class 3 dealer in NFA, but not for an individual owner. After submitting your paperwork, the process generally takes from three to six months. Once you receive your signed form 4 with tax stamp back from the ATF, you’re eligible to take possession of your firearm. If it is being shipped, it must be shipped to a class III FFL, except that silencers, for residents of the state of Texas, may be shipped directly to them.

You may even manufacture your own NFA Firearms, with the exception of machine guns which are illegal for an individual to manufacture. However, before starting, you must pay a manufacturing tax of $200. Of course, you’ll also have to pay a $200 registration tax, so it might be more cost effective to simply buy your NFA Firearm from a licensed manufacturer/dealer.

According to The NFA Handbook, “Violations of the Act are punishable by up to 10 years in federal prison and forfeiture of all devices or firearms in violation, and the individual’s right to own or possess firearms in the future. The Act provides for a penalty of $10,000 for certain violations. A willful attempt to evade or defeat a tax imposed by the Act is a felony punishable by up to five years in prison and a $100,000 fine ($500,000 in the case of a corporation or trust), under the general tax evasion statute. For an individual, the felony fine of $100,000 for tax evasion could be increased to $250,000.” Ouch!

Sound suppressors are becoming more popular. They should be legal for health reasons as they were before NFA. You could generally buy them in the local hardware store. No one wants to sacrifice their hearing to pursue shooting sports, and we shouldn’t have to.

As for SBRs, a host of manufacturers are now offering non NFA large pistols that, with a single point sling and red dot optic, can substitute for an SBR in home defense applications.

Maintaining our Second Amendment rights will still be a struggle but the pendulum seems to be swinging in our favor. In the meantime, if you want an NFA Firearm, go out and get one. It’s your right.

The misunderstandings about the National Firearms Act (NFA) go back a long way. All the way to Prohibition, in fact, to gang warfare and shootings like the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre:

It was February 14th, 1929. The Irish gangster Bugsy Moran, one of Al Capone’s fiercest enemies, ran his bootlegging operation out of a garage on the north side of Chicago. Men dressed as policemen entered the garage and told the seven men they found there that they were under arrest. The men were then lined up in front of a brick wall and unceremoniously gunned down. Al Capone was conveniently at his home in Florida at the time.

The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre was followed four years later, February 15th, 1933, by an assassination attempt on President Roosevelt by Giuseppe Zangara in Miami. Roosevelt escaped unharmed but the mayor of Chicago, Anton Cermak, died from his wounds. The people had had enough.

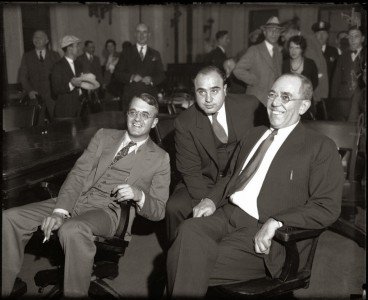

Big Al with his attorneys during his 1931 trial for tax evasion. They were smiling but he went to prison.

WHAT IS NFA?

In 1934 Congress passed the National Firearms Act (NFA). The purpose of the law was to curtail transactions in firearms favored by organized crime (NFA Firearms). These included machine guns, silencers, and sawed-off shotguns. Because the law was passed supposedly as an exercise of Congress’ authority to tax, that was the mechanism used to accomplish their real goals. The transfer tax on an NFA Firearm was set at $200. Adjusted for inflation, that was equivalent to $3,557.76 in 2015 dollars. Congress felt that was enough to curtail sales of these firearms. Of course, it was pocket change for the big gangs of the day. However, it did make it nearly impossible for everyday citizens to buy them. The takeaway here is that, although it priced these items out of the reach of ordinary citizens, it did not make them illegal as long as they were properly registered and the tax was paid.The NFA was updated through Title II of the Gun Control Act (GCA) of 1968, and the misnamed Firearm Owner’s Protection Act (FOPA) of 1986. FOPA made it illegal for anyone other than the military and law enforcement to possess a machinegun except for those already registered prior to May 19, 1986. It also made components of NFA Firearms, like silencer parts and fully automatic trigger packs, into NFA Firearms under the law. It was justified as an “intent to build” an NFA Firearm.

SO WHAT ARE TODAY’S NFA FIREARMS AND HOW CAN YOU LEGALLY OWN THEM UNDER FEDERAL LAW?

NFA Firearms Categories: (National Firearms Handbook https://www.atf.gov/firearms/national-firearms-act-handbook)- Machine guns – any gun that can fire more than one shot with a single pull of the trigger

- Short-barreled rifles (SBRs) – any gun with a buttstock and with a rifled barrel less than 16” or overall length of under 26”

- Short-barreled shotguns (SBSs) – similar to an SBR but with a smooth bore barrel less than 18” or overall length less than 26”

- Suppressors – any portable device designed to muffle or disguise the report of a portable firearm

- Destructive Devices (DDs) – grenades, bombs, bazookas, poison gas weapons, etc. Any firearm with a bore diameter of more than 0.50” except for shotguns.

- Any other weapon (AOW) – weapons or devices which can be concealed on the body and which fire a projectile through an explosive force. Includes pen guns, cane guns, lighter guns, etc. In 1960 the tax for AOWs was reduced to $5.

- Parts associated with NFA Firearms – suppressor baffles, drop-in fully automatic trigger sears, etc.

REGISTRATION,PURCHASES, TAXES and TRANSFERS

The most common NFA Firearms are machine guns, SBRs, and silencers. It is completely legal under federal law to buy, own, and shoot these items. However, some state and local laws ban ownership so check with local law enforcement before making a purchase. In addition, prior to completing a purchase you have to first register the item in the NFA Registry with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (BATFE or simply ATF), and pay the $200 registration tax. Fortunately the tax has not changed since 1934. (At last, something that has benefitted from inflation!)

If

you want to avoid the paperwork, there are semi-auto versions of the

old classics that are still fun to shoot. This Thompson pistol is made

by Auto Ordnance.

The process is fairly simple if time consuming. As an individual, you must obtain approval from the ATF, obtain a signature from the Chief Law Enforcement Officer (CLEO) who is the county sheriff or city or town chief of police (not necessarily permission), pass an extensive background check to include submitting a photograph and fingerprints, fully register the firearm, receive ATF written permission before moving the firearm across state lines, and pay a tax. The request to transfer ownership of an NFA item is made on an ATF Form 4. (https://www.atf.gov/file/61546/download)

An alternate method of registering an NFA Firearm is as a corporation, trust, or other legal entity. When the paperwork to request transfer of an NFA item is initiated by an officer of a corporation, a signature from local law enforcement is not required, and fingerprint cards and photographs do not need to be submitted with the transfer request. Therefore, an individual who lives in a location where the chief law enforcement officer will not sign a transfer form, for example, can still own an NFA item if he or she owns a corporation or trust. This method has downsides, since it’s the corporation (and not the principal) that owns the firearm. Thus, if the corporation ever dissolves, it must transfer its NFA to the owners. This event would be considered a new transfer and would be subject to a new transfer tax.

When buying your first silencer or sound suppressor (the terms are used interchangeably), I recommend the Silencer Shop . I have no affiliation with them but they simplified the process for me when I bought my first silencer. They will take you by the hand and lead you through the steps. They also have forms and can help you set up a trust if you decide to go that route. Very responsive and professional group of people.

You can also get forms and instructions through the ATF website: https://www.atf.gov/resource-center/forms-library, and online through sites like https://www.guntrustlawyer.com/form4.

You do not need a “Class III FFL” or any other license. An FFL is required as a prerequisite to become a Special Occupation Taxpayer (SOT): Class 1 importer, Class 2 manufacturer-dealer or Class 3 dealer in NFA, but not for an individual owner. After submitting your paperwork, the process generally takes from three to six months. Once you receive your signed form 4 with tax stamp back from the ATF, you’re eligible to take possession of your firearm. If it is being shipped, it must be shipped to a class III FFL, except that silencers, for residents of the state of Texas, may be shipped directly to them.

You may even manufacture your own NFA Firearms, with the exception of machine guns which are illegal for an individual to manufacture. However, before starting, you must pay a manufacturing tax of $200. Of course, you’ll also have to pay a $200 registration tax, so it might be more cost effective to simply buy your NFA Firearm from a licensed manufacturer/dealer.

PENALTIES

While the registration process for NFA Firearms is a hassle and many of us think it’s unconstitutional, this isn’t something you want to treat lightly. It is currently the law of the land. Breaking the law will put you in serious doo doo. And there’s no reason to risk it. Sure $200 seems like a lot of money and who wants to be on a registration list? But it’s not $3,500 like it was in 1934 (thanks to inflation) so consider it a bargain.According to The NFA Handbook, “Violations of the Act are punishable by up to 10 years in federal prison and forfeiture of all devices or firearms in violation, and the individual’s right to own or possess firearms in the future. The Act provides for a penalty of $10,000 for certain violations. A willful attempt to evade or defeat a tax imposed by the Act is a felony punishable by up to five years in prison and a $100,000 fine ($500,000 in the case of a corporation or trust), under the general tax evasion statute. For an individual, the felony fine of $100,000 for tax evasion could be increased to $250,000.” Ouch!

THE FUTURE

No one knows what the future will bring. However there are some positive signs. Who needs to pay $15,000 for a pre-ban machine gun when you can get a non-NFA trigger like a Tac-Con 3 MR or Tac-Con AK47 Raptor that allows full automatic-like fire. (You still have to pull the trigger separately for each shot but the trigger helps you do that more effectively.) And there are less expensive devices like the GAT, Hellfire, Tac Trigger, and Slide Fire bump fire stock. Maybe as these proliferate, politicians can be persuaded that that they’re just hurting our gun manufacturers with a ban that no longer makes sense.Sound suppressors are becoming more popular. They should be legal for health reasons as they were before NFA. You could generally buy them in the local hardware store. No one wants to sacrifice their hearing to pursue shooting sports, and we shouldn’t have to.

As for SBRs, a host of manufacturers are now offering non NFA large pistols that, with a single point sling and red dot optic, can substitute for an SBR in home defense applications.

Maintaining our Second Amendment rights will still be a struggle but the pendulum seems to be swinging in our favor. In the meantime, if you want an NFA Firearm, go out and get one. It’s your right.